Louisville and Oakland (Special to ZennieReport.com) – The City Of Oakland has wound-up oweing Insight Terminal Solutions, the developers of the Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal, as much as $678 Million to close the giant string of court losses the City of Oakland has sustained in its illegal quest to get around a contract it signed to allow coal to be transported via the planned OBOT to overseas destinations in the Pacific Rim.

As Judge Joan A. Lloyd explains

“Based on applicable California law, Plaintiff has proven damages with reasonable certainty,through financial records, expert testimony, and evidence of financing commitments. Defendant’s expert through his deposition conceded damages to Plaintiff in an amount no less than $230 million. Plaintiff’s proof of damages is $673,658,000 reduced by $20 million paid to assume the business and Sublease, exclusive of pre judgment interest (at a rate of 7.00% per annum beginning September 24, 2018), fees, and costs that may also be awarded. This disparity leaves the Court with an issue of fact as to the appropriate amount of damages due Plaintiff.”

What follows is the exact copy of the court case filing and its conclusion.

Three matters are before the Court for consideration: (i) a Motion for Summary Judgment[Doc.116] filed by Plaintiff, Debtor Insight Terminal Solutions, LLC (“ITS” or “Plaintiff” or“Debtor”), which is opposed by Defendant, City of Oakland (“the City” or “Defendant”); (ii) the City’s Motion for Summary Judgment [Doc. 118], which is opposed by ITS; and (iii) ITS’s Motionfor Judicial Notice Relating to ITS’s Motion for Summary Judgment [Doc. 117], which is opposed by the City.

For the reasons set forth below, this Court enters its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law Addressing Competing Motions for Summary Judgment and Related Motion for Judicial Notice in accordance with Rule 9033 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure, which support

(a) GRANTING the Motion for Judicial Notice, (b) GRANTING the Motion for Summary Judgment, in part, filed by ITS, and (c) DENYING the Motion for Summary Judgment filed by the City.

PROCEDURALANDEVIDENTIARYBACKGROUND

On March 11, 2024, Plaintiff filed its Complaint for Damages. On December 19, 2024, after unsuccessfully seeking dismissal of this proceeding (seeMemorandum Opinion and Order Motion to Dismiss [Doc. 56] [“Dismissal Order”]), Defendant filed an Answer [Doc. 64] denying

and contesting the allegations and claims asserted by ITS in the Complaint.

On January 29, 2025, the Court entered an order directing the parties to “conduct discovery within one hundred twenty (120) days from the date of this order.” [Doc. 77]. The Order was subsequently amended via a joint stipulation from the parties and agreed order by this Court [Doc. 93] and subsequent agreement of the parties (see Notice and Text Order [Doc. 106]) to extend the discovery completion deadlines to June 30, 2025. On July 1, 2025, discovery in this proceeding closed.

After completion of discovery by the parties, on July 10, 2025, the Court conducted a telephonic pre-trial conference, which resulted in the issuance and entry of a Scheduling Order for Dispositive Motions entered by the Court on July 15, 2025 [Doc. 115]. The parties, in accordance with the Scheduling Order, completed the following filings (collectively, the “Summary Judgment

Filings”):

- Doc. 116 – ITS’s Motion for Summary Judgment against the City of Oakland dated July 28, 2025 (“ITS Motion”)

- Doc. 117 – ITS’s Motion for Judicial Notice Relating to ITS’s Motion for Summary Judgment dated July 28, 2025 (“RJN”)

- Doc. 118 – The City’s Motion for Summary Judgment against ITS dated July 28, 2025 (“City Motion”)

- Doc. 122 – ITS’s Objection to the City’s Motion for Summary Judgment dated August 5, 2025

- Doc. 123 – The City’s Objection to ITS’s Motion for Summary Judgment dated August 5, 2025

- Doc. 124 – The City’s Response to Motion for Judicial Notice Relating to Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment dated August 5, 2025

- Doc. 129 – The City’s Reply to ITS’s Objection to the City’s Motion for Summary Judgment dated August 20, 2025

- Doc. 130 – ITS’s Reply to the City’s Objection to ITS’s Motion for Summary Judgment dated August 20, 2025

- Doc. 131 – ITS’s Reply to the City’s Response to ITS’s Separate Statement of Undisputed Facts dated August 20, 2025

- Doc. 132 – ITS’s Reply to the City’s Objections to Evidence Submitted in Support of ITS’s Motion for Summary Judgment dated August 20, 2025

- Doc. 133 – ITS’s Reply to Response to Motion for Judicial Notice Relating to ITS’s Motion for Summary Judgment dated August 20, 2025

- Doc. 135 – The City’s Sur-Reply Relating to Filings at Docs. 130 and 133 dated August 26, 2025

On August 27, 2025, the Court conducted a hearing for oral arguments by the parties concerning the Summary Judgment Filings. (See generallyNotice of Hearings [Docs. 125–26].) Then, on August 29, 2025, the Court entered an Order [Doc. 136] directing the parties to submit Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law by September 17, 2025. On September 17, 2025, the parties submitted their respective Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in accordance with the August 29, 2025 Order.

Thereafter, the Court reviewed and considered the Summary Judgment Filings, the arguments and information presented by the parties’ attorneys during the August 27, 2025 hearing,

and the parties’ competing Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law before rendering the Court’s own Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law as set forth below.

FINDINGSOFFACT

The undisputed relevant facts set forth below are consistent with those identified in Plaintiff’s Moving Party’s Separate Statement of Undisputed Facts [Doc. 116-30] (“SOF”), and are

supported significantly by (i) the Statement of Decision entered by the Honorable Noël Wise of the Superior Court of California, County of Alameda, on November 22, 2023 (“Statement of

Decision”) (RJN, Ex. 1); (ii) the Judgment entered by the Honorable Noël Wise of the Superior

Court of California, County of Alameda, on January 23, 2024 (RJN, Ex. 2) (“Judgment”); and (iii)

the Opinion of the Court of Appeal of the State of California, First Appellate District, Division Two, on June 27, 2025, published as Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC v. City of Oakland, 112 Cal. App. 5th 519 (Cal. Ct. App. 2025) (RJN, Ex. 3) (“Opinion”) (collectively, the “Judicial

Decisions”).

The Court finds that the following facts are not in material dispute:

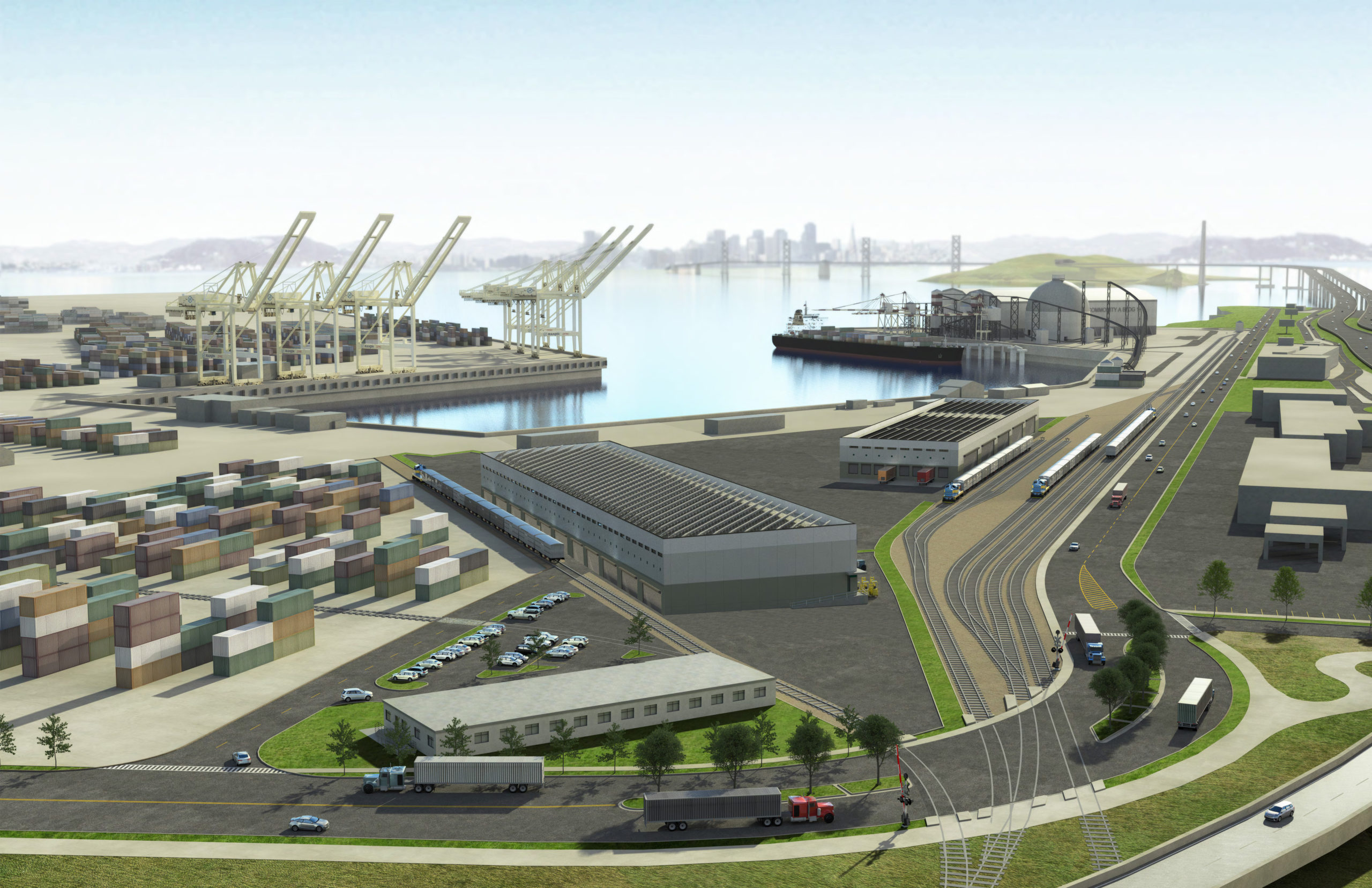

- In the Complaint [Doc. 1] filed on March 11, 2024, which initiated the above-styled adversary proceeding, Plaintiff asserts two causes of action arising from the City’s alleged obstruction of the development of a rail-to-ship bulk commodity terminal (“Terminal”) located at

a portion of the former Oakland Army Base known as the West Gateway (“West Gateway”).

(Compl. ¶ 1.)

- The first cause of action asserted by ITS is a claim for tortious interference with prospective economic advantage, by which ITS seeks to hold the City accountable for its alleged interference with Plaintiff’s third-party contract and prospective economic advantage and the

damages directly resulting therefrom, which Plaintiff believes to be close to a billion dollars. (SeeCompl. ¶¶ 65–74.)

- The second cause of action asserted by ITS is a claim for tortious interference with contract, by which ITS seeks to hold the City accountable for its improper acts and omissions with respect to the Debtor’s utilization and monetization of the Sublease to develop a rail-to-ship bulk commodity terminal at the former Oakland Army Base, the damages from which directly led to the Debtor filing its bankruptcy petition with this Court. (SeeCompl. ¶¶ 75–88.)

- These causes of action are based upon the following factual allegations asserted by ITS in its Complaint and established in the record through subsequent filings identified below.

TheBulkCommodityMarineTerminal

- Plaintiff’s sublandlord, Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal, LLC (“OBOT”),

and the City executed a series of contracts, including the Army Base Gateway Development Project Ground Lease for West Gateway, dated February 16, 2016 (as amended, “Ground Lease”) that

vested in OBOT the right to develop and operate the Terminal. (SOF ¶¶ 1–5.) When coal became politically disfavored, the City passed an ordinance that prohibited the handling, storage and transportation of coal within the City (“Ordinance”), and applied the Ordinance only to the

Terminal through a resolution (“Resolution”). (SOF ¶ 6.) Thereafter, OBOT filed a federal civil

action against the City challenging the validity of the Ordinance and Resolution. (SOF ¶ 7.)

The Federal Lawsuit (OBOT I)

- Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC v. City of Oakland, 321 F. Supp. 3d 986 (N.D. Cal. 2018), aff’d, 960 F.3d 603 (9th Cir. 2020) (“OBOT I”) clarified that OBOT had a vested

contractual right to develop and operate a Terminal through which coal could be transferred and that the City was enjoined from applying the Ordinance to the Terminal, and the Resolution was found void. (SOF ¶ 8.)

TheSublease

- The City understood that OBOT would be subleasing the Terminal to a third-party. (SOF ¶ 9.) The Ground Lease includes express provisions that allow OBOT to sublease the Terminal and that require the City to, among other things, provide (upon request) an estoppel certificate and non-subordination agreement that would be relied upon by third parties. (SOF ¶¶ 10–12.) To expand existing coal exports, on September 24, 2018, OBOT and Plaintiff entered into the Army Base Gateway Redevelopment Project Sublease for West Gateway (“Sublease”),

which granted Plaintiff the right (and obligation) to develop and operate the Terminal. (SOF ¶¶ 14, 17.) OBOT, on behalf of ITS, (i) provided a copy of the executed Sublease to the City; (ii) asked the City to provide a valid estoppel certificate for use by ITS; and (iii) asked the City to enter into a non-disturbance agreement with ITS. (SOF ¶¶ 11–12, 19–20.)

- Before and after execution of the Sublease, ITS (including through its predecessor- in-interest) took steps to advance the development of the Terminal, including by requesting meetings with and submitting applications to various City employees. (SOF ¶¶ 16, 21–22.) After OBOT I, however, the City’s leadership enacted a plan to stop the Terminal from moving forward. (SOF ¶¶ 23–25.) To enact the plan, various City officials and employees—including, without limitation, the Mayor, City Councilmembers, the City Attorney and her staff (including, without limitation, Bijal Patel), the City Administrator and her staff, and the Director of Building and Planning and his staff—took actions to interfere with and frustrate the development of the Terminal. (SOF ¶¶ 24–26, 32–36, 40–41.) For example, the City Attorney, Barbara Parker delivered a notice of unmatured event of default, dated September 21, 2018, claiming that OBOT was in default of the Ground Lease and conditioned a cure on an agreement not to ship coal. (SOF

¶ 26; [Doc. 116-6].) On October 23, 2018, the City Attorney issued a Notice of Default, claiming

that OBOT was in default of the Ground Lease and, on November 22, 2018, the City Attorney issued a notice claiming to have terminated the Ground Lease. (SOF ¶¶ 38, 41; [Doc. 116-7].) The Director of Building and Planning, William Gilchrist, refused to process design permit applications and canceled scheduled meetings without rescheduling the same. (SOF ¶ 34; [Doc. 116-14].) Additionally, the City Attorney and her staff (i) refused to acknowledge the Sublease, (ii) issued an estoppel certificate incorrectly claiming the Ground Lease was in default, (iii) refused to execute a non-disturbance agreement with ITS, and (iv) ignored business and financial information provided by ITS. (SOF ¶¶ 27–28, 31–35, 40; Docs. 116-9, 116-11, 116-13, 116-16.)

- Because the City refused to honor its obligations, ITS was unable to access additional committed capital and pay back its loan (“AWL Loan”) to Autumn Wind Lending, LLC

(“AWL”), and Plaintiff was forced to file a petition for chapter 11 bankruptcy relief with this Court.

(SOF ¶¶ 49–50.) For example, Plaintiff had funding commitments from (a) GACP Finance Co., LLC (“GACP”) which had approved an approximate $40 million loan to ITS and (b) the State of

Utah, which had approved an approximate $53 million in funding to ITS—on the condition that the City issue the non-disturbance agreement and a clean estoppel certificate. (SOF ¶¶ 46–49.) However, ITS could not obtain these funds due to the City’s refusals to honor its obligations and the plan to interfere with the Terminal effectuated by the City employees. (SOF ¶¶ 51–54.)

StateLawsuitandtheCity’sPost-StateLawsuitConduct

- On December 4, 2018, OBOT filed a lawsuit against the City in the Superior Court of California, County of Alameda (“OBOT II”) seeking relief for the City’s improper Ground Lease

termination. (SOF ¶ 42.). The initial complaint in OBOT IIalleged twelve causes of action: “breach of contract (first through third causes of action); fraud (fourth cause of action); intentional and negligent interference with contract and prospective economic advantage (fifth through tenth

causes of action); declaratory relief (eleventh cause of action); and specific performance (twelfth

cause of action).” See Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC v. City of Oakland, 54 Cal. App. 5th 738, 745 (Cal. Ct. App. 2020).

- In response to Defendant’s demurrer as to all causes of action, the Superior Court dismissed the tort claims in the initial complaint with leave to amend. Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC, 54 Cal. App.5th at 748; (Declaration of Skyler M. Sanders in Support of Plaintiff’s Objection to Defendant City of Oakland’s Motion for Summary Judgment [Doc. 122-1] [“Sanders

Decl. II”], Exs. 6–8.) Consequently, OBOT filed an amended complaint, which excluded the tort

claims and only asserted six causes of action: breach of contract (first and second causes of action); anticipatory breach (third cause of action); breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing (fourth cause of action); declaratory relief (fifth cause of action); and specific performance (sixth cause of action). Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, 112 Cal. App. 5th at 530.

- Following a bench trial, the California Superior Court entered the Statement of Decision detailing the City’s bad faith acts and omissions. Then, on January 23, 2024, the Judgment was entered against the City, finding, in pertinent part, that the City acted in bad faith when it improperly attempted to terminate the Ground Lease instead of substantively responding to OBOT, ITS or Millcreek Engineering (ITS’s engineer). (SOF ¶¶ 43–44.) The Statement of Decision and Judgement were subsequently upheld on appeal. (SOF ¶ 45.) Despite the rulings against it by multiple courts, the City and its employees continue with their pattern of interference, with the newly elected Mayor, Barbara Lee, doubling down in 2025 that she will do everything in her power to stop development of the Terminal. (Sanders Decl. II, Exs. 4–5.)

- The preceding events and conduct by the City constitute continuing interference with the Plaintiff’s ability to monetize the Sublease, and finance, develop and operate the Terminal, causing the Plaintiff substantial monetary damages. (SOF ¶¶ 54–56.)

ITS’sPendingBankruptcyCase

- On or about November 3, 2020, the Court entered an Order [Main Case Doc. 245- 1] (“Confirmation Order”), which confirmed Autumn Wind Lending, LLC’s Chapter 11 Plan of

Reorganization for the Bankruptcy Estate of Debtor Insight Terminal Solutions, LLC Pursuant to Bankruptcy Code Section 1121(c)(2) (the “Plan”). (SOF ¶ 57.) The Plan and Confirmation Order

allowed AWL to assume all rights and obligations of ITS under the Sublease for total consideration of approximately $20 million. (Id.; see alsoConfirmation Order [Main Case Doc. 379] ¶¶ 6.b., 15.) Paragraph 14 of the Confirmation Order expressly preserved Plaintiff’s right to bring any “Litigation Claims” before this Court, and Paragraph 27 of the Confirmation Order included broad jurisdictional retention language. (Confirmation Order ¶¶ 14, 27; see alsoPlan [Main Case Doc. 245-1] at Article IX.)

- Before the Confirmation Order was approved, the City appeared in the chapter 11 case and filed the City’s Confirmation Objection on August 4, 2020 [Main Case Doc. 276] (“Confirmation Objection”). (SOF ¶ 58.) In the Confirmation Objection, the City raised two

targeted points of opposition to the proposed Debtors’ Plan of Reorganization and AWL’s Plan: (i) the plans did not appear to meet the feasibility requirements of § 1129(a)(11); and (ii) ITS’s plan was not proposed in good faith as required by § 1129(a)(3) (Confirmation Obj. at 9–11.) In addition, the Confirmation Objection included an objection to the Plan’s assumption of the Sublease, the City representing that the Ground Lease was terminated and the Sublease was void. (Confirmation Obj. at 11–12.). In support of its explicit and substantive opposition to AWL’s assumption of the Sublease, the City argued as follows:

To be clear, ITS and the City are not in privity of contract with one another. ITS’ rights under the aptly titled [Sublease] are entirely dependent on OBOT’s rights under the Ground Lease—issues

which are squarely before the California courts for adjudication . . .

As explained above, the City takes the position that the [Sublease] is not subject to assumption in connection with confirmation of the competing Plans . . . .

In the instant cases, neither the Debtors nor AWL may resurrect and assume the [Sublease] if the Ground Lease terminated prepetition. There can be no dispute that the termination of the Ground Lease is the subject of active litigation. If the California court determines that the Ground Lease was, in fact, terminated in 2018, there is nothing left for the plan proponents to assume.

(Confirmation Obj. at 3, 11–12; see alsoSOF ¶ 58.) The Confirmation Objection contains no objection to the Plan’s Retention of Jurisdiction provisions in Article IX.1 Of additional note is ITS’s statements in the bankruptcy case that “[t]he root cause” for ITS seeking chapter 11 bankruptcy was the “Oakland Overburden,” described as the “[C]ity officials[’] oppos[ition] [to] the transportation and export of coal from the Project Terminal that is contemplated under ITS’s development and operation plans for the Project under the Sublease.” (Obj. to Mot. to Dismiss [Main Case Doc. 61], ¶ 28.) ITS went on to explain to the Court:

[I]f the Debtors cannot consensually remediate the Oakland Overburden by collaborating and partnering with the City of Oakland, then the Debtors further assert that this Court is or can be empowered adjudicate or otherwise address the West Gateway Master Development Agreement dispute, which directly affects the Sublease that stems from the Agreement, along with any other Oakland Overburden issues.

1 Article IX provides: Notwithstanding the entry of the Confirmation Order and the occurrence of the Effective Date, the Bankruptcy Court shall retain non-exclusive jurisdiction of all matters arising out of, and related to, the Chapter 11 Case and the Plan, including jurisdiction to: . . . [1] resolve any matters related to . . . Unexpired Leases . . . [5] issue and implement orders in aid of execution, implementation, or consummation of the Plan . . . [8] hear and determine disputes arising in connection with the interpretation, implementation, or enforcement of this Plan or the Confirmation Order, including disputes arising under agreements, documents, or instruments executed in connection with this Plan and disputes arising in connection with any Person or entity’s obligations incurred in connection with the Plan . . . [12] hear any other matter not inconsistent with the Bankruptcy Code [15] enforce all orders previously entered by the Bankruptcy Court.

After the Effective Date, the Bankruptcy Court shall retain jurisdiction with respect to each of the foregoing items and all other matters that were subject to its jurisdiction prior to the Confirmation Date . . . .

(Plan [Main Case Doc. 245-1] at Article IX; see also Conf. Order [Main Case Doc. 379] ¶ 27.)

(Id. at ¶ 35.) Unable to consensually remediate the Oakland Overburden, Plaintiff filed the Complaint.

TheAdversaryProceeding’sCausesofAction

- On March 11, 2024, Plaintiff filed the Complaint seeking to hold the City accountable for its interference with Plaintiff’s third-party contract and prospective economic advantage and the damages directly resulting therefrom, in an amount of $673,658,000. (SOF ¶ 55; see also generallyComplaint.)

LEGALANALYSIS

Plaintiff’sMotionForJudicialNotice

As a preliminary matter, necessary to resolve before the Court evaluates the competing motions for summary judgment, the Court must first address the RJN so that the Court can identify what evidence from the Judicial Decisions it should or should not consider via judicial notice when evaluating the competing motions.

Plaintiff’s undisputed facts and supporting evidence (as identified in the SOF) rely heavily on the Judicial Decisions. Relatedly, Plaintiff filed the RJN, asking this Court to take judicial notice of the Judicial Decisions, as well as three documents previously filed with this Court in the chapter 11 bankruptcy case (“Bankruptcy Documents”). Defendant does not object to this Court taking

judicial notice of the documents identified in the RJN. Instead, Defendant objects to the Court’s reliance upon the documents for the truth of the matter asserted therein.

Requests for judicial notice of adjudicative facts are governed by Federal Rule of Evidence 201, which provides, in pertinent part, that a court may “judicially notice a fact that is not subject to reasonable dispute” because it is generally known in the court’s jurisdiction or “can be accurately and readily determined from sources whose accuracy cannot reasonably be questioned.”

Fed. R. Evid. 201. Because Defendant does not oppose the Court taking notice of the documents identified in the RJN, the Court will take judicial notice of the same.

Next, the Court analyzes Defendant’s argument that once judicially noticed, the Court cannot rely upon the documents for the truth of the matter asserted therein. In support of its position, Defendant cites multiple cases, primarily relying on Adkisson v. Jacobs Eng’g Group,2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 243188, at *23 (E.D. Tenn. Aug. 6, 2018); Liberty Mut. Ins. Co. v. Rotches Pork Packers, Inc., 969 F.2d 1384, 1388–89 (2d Cir.1992); United States v. Jones, 29 F.3d 1549,

1553 (11th Cir. 1994); and United States v. Collier, 68 F. App’x 676, 683 (6th Cir. 2003).

While it is true that a court cannot accept as true the facts set forth in any document filed with the court, it has long been understood that a court can accept as true facts found and conclusions reached included in orders, judgment and findings of facts and conclusions of law. Farmers Bank & Tr. Co. v. Wells(In re Wells), 536 B.R. 264, 267 n.2 (Bankr. E.D. Ark. 2015) (citing 2 Barry Russell, Bankruptcy Evidence Manual § 201.7 (2014–15 ed. 2014)); Garcia v. Sterling, 176 Cal. App.3d 17, 22 (Cal. Ct. App. 1985) (“A court may take judicial notice of the existence of each document in a court file, but can only take judicial notice of the truth of facts asserted in documents such as orders, findings of fact and conclusions of law, and judgments.”) This conclusion is made possible, in part, by the doctrine of collateral estoppel (also called issue preclusion). In re Snider Farms, Inc., 83 B.R. 977, 986–87 (Bankr. N.D. Ind. 1988) (“Thus, while a Court may take judicial notice of the existence of each document in the Court’s file it may only take judicial notice of the truth of facts asserted in documents such as orders, judgments, and findings of fact and conclusions of law because of the principles of collateral estoppel, res judicata, and the law of the case.”). Stated otherwise, “[w]here a party defendant clearly had his day in court on the specific issue brought into litigation within the later proceeding, the non-party plaintiff can

rely upon the doctrine of collateral estoppel to preclude the relitigation of that specific issue.” Aabbott [sic] v. E. I. Du Pont De Nemours & Co. (In re E.I. Du Pont De Nemours & Co. C-8 Pers. Inj. Litig.), 54 F.4th 912, 922 (6th Cir. 2022) (citation modified).

The Sixth Circuit has long held that a plaintiff, even if not a party to the prior action, may invoke collateral estoppel, including on summary judgment, at the court’s discretion. May v. Oldfield, 698 F. Supp. 124, 125–26 (E.D. Ky. 1988) (“Both the federal common law and the Restatement of Judgments approve of the use of offensive collateral estoppel.”). When used against a defendant who was unsuccessful in a prior action on an adjudicated issue, it is called “offensive collateral estoppel.” Mustaine v. Kennedy(In re Kennedy), 243 B.R. 1, 9–11 (Bankr. W.D. Ky. 1997). For a plaintiff—including one who was not a party in the prior action (i.e., non- mutual)—to use offensive collateral estoppel, the Supreme Court instructs courts to weigh four considerations.

First, courts should avoid applying non-mutual offensive collateral estoppel where it would encourage “a ‘wait and see’ attitude” among potential plaintiffs hoping “that the first action by another plaintiff will result in a favorable judgment.” Parklane Hosiery Co., 439 U.S. 322, 330, 99 S. Ct. 645 (1979). (See infra, page 9, paragraph 15, where Defendant admits ITS’ rights under its sublease with OBOT were entirely dependent upon OBOT’s rights under the Groundlease . . .). Second, courts should not use the doctrine if the defendant, did not have a reason “to defend vigorously, particularly if future suits [were] not foreseeable.” Id. Third, the doctrine should not apply “if the judgment relied upon as a basis for the estoppel is itself inconsistent with one or more previous judgments in favor of the defendant.” Id. Defendant has not proven to the Court any inconsistent judgments against it. Fourth, courts should avoid the use of non-mutual offensive collateral estoppel if the later action would give “the defendant procedural opportunities

unavailable in the first action that could readily cause a different result.” Id.at 331. Again, Defendant, has not tendered any evidence to make such claims in this action.

The Court considered each of these factors and determine that none of these factors preclude Plaintiff from utilizing offensive collateral estoppel. The Court further determines that Defendant is barred from relitigating issues resolved in the Judicial Decisions and this Court may rely on these factors for the truth of the matters they establish.

The Judicial Decisions are judgments, orders, and findings of fact and conclusions of law not readily subject to reasonable dispute because they are final judgments on the merits. Additionally, permitting the use of non-mutual collateral estoppel does not promote a “wait-and- see” approach by Plaintiff. OBOT IIwas a breach of contract action between OBOT and Defendant, and the City concedes it was not (and is not) in contractual privity with Plaintiff under the agreement at issue in OBOT II. (SeeSOF ¶¶ 30, 58.) As a result, Plaintiff would have lacked standing to pursue claims in OBOT II—in Defendant’s own words, the rights of Plaintiff under the Sublease were entirely conditioned upon the outcome of OBOT II. (Id.) Plaintiff’s non-joinder in OBOT IIcannot, therefore, be classified as a “wait-and-see” tactic.

The procedural history of OBOT IIdemonstrates that Defendant engaged in a vigorous defense of the allegations levied against it: that Defendant improperly attempted to terminate the Ground Lease and acted in bad faith. Indeed, Defendant has used nearly every available procedural opportunity at its disposal to mount a defense including filing a motion to dismiss (demurrer), anti- SLAPP motion, anti-SLAPP appeal, motion for summary judgment, a 35-day bench trial, and appeal of the Statement of Decision and Judgment. Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC, 112 Cal. App. 5th at 529–31. In each instance, as well as in OBOT I, the City lost, so there is no other judgment in Defendant’s favor creating a reasonable dispute. As a result, the four considerations

(and judicial economy) weigh in favor of the Court allowing Plaintiff to use offensive collateral estoppel—there is no need by the Court to rehash these same arguments. Defendant’s petition to the California Supreme Court for additional review of the Judicial Decisions does not change this analysis. See Irvin v. Faller(In re Faller), 547 B.R. 766, 770 (Bankr. W.D. Ky. 2016) (“[T]he Circuit Court judgments were final for the purposes of collateral estoppel, despite the potential for appeal.”)

Whether it is by judicial notice of the finally adjudicated Judicial Decisions or the related offensive collateral estoppel, the Court can and will exercise its discretion to review the Judicial Decisions for the truth of the matter asserted therein.

The cases cited by Defendant in support of its position are unpersuasive. In Adkisson, the court would not take judicial notice of any facts contained in a contract, safety booklet, administrative order and EPA publications before any case between the parties went to trial. 2018

U.S. Dist. LEXIS 243188, at *23–25. As set forth above, the Judicial Decisions are finally adjudicated legal decisions against Defendant entered after a 35-day bench trial. In Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., the court could not accept as true the facts contained in prior orders because the party against whom the facts were to be introduced was not a party to the action in which the order was issued, thus collateral estoppel did not apply. 969 F.2d at 1388–89. To the contrary, Defendant was a named party in OBOT Iand OBOT IIand, as a result and as further set forth above, collateral estoppel applies. Unlike the Judicial Decisions, which are fully adjudicated decisions, the court in Jones would not accept as true findings that were not fully adjudicated in a prior action. 29 F.3d at 1553. In Collier, the appellate court found that the district court did not abuse its discretion when “tak[ing] judicial notice of the bankruptcy judgment as evidence of the proceeding, as well as several facts from that proceeding.” 68 F. App’x at 683. What the Collier court clarified was that

the court was not required to notice the findings for the truth of the matter asserted therein. Id. As

explained above, the Court exercises its discretion to take judicial notice of the Judicial Decisions and, under the doctrine of collateral estoppel, will not permit re-litigation of issues already resolved in a prior action against Defendant.

With respect to the Bankruptcy Documents, Federal Rule of Evidence 201 permits a court to take judicial notice of its own court records. See Fed. R. Evid. 201(c). Although the City objects to authenticity and admissibility of these documents, the Court will nonetheless admit the Bankruptcy Documents for reasons addressed further below.

Accordingly, the RJN is granted in full, and the Court will consider these documents to evaluate the merits of the parties’ respective motions.

TheCompetingMotionsforSummaryJudgment

- Summary Judgment Standard of Review Legal Standard for Evaluating the Proposed Grounds for Dismissal

Under Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, made applicable through Rule 7056(b) of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure, the movant has the burden to identify evidence in the record that demonstrates an absence of a genuine dispute of material fact so that the court can grant the movant’s motion for summary judgment. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 322 (1986). “The moving party may support the motion for summary judgment with affidavits or other proof ….” Town & Country Equip., Inc. v. Deere & Co., 133 F. Supp. 2d 665, 667 (W.D. Tenn. 2000). “Only disputes over facts that might affect the outcome of the suit under the governing law will properly preclude the entry of summary judgment. Factual disputes that are irrelevant or unnecessary will not be counted.” Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986). After reviewing the entire statement of facts advanced by the parties, as well as the other

evidence submitted by the parties, the Court finds that there are no material and relevant facts at issue.

II.Plaintiff’sEvidenceSubmittedinConnectionwithitsMotionisAdmissible

In addition to the facts already determined in the RJN documents, ITS submits evidence in support of the ITS Motion, including (i) an expert report and reply report by Plaintiff’s damage expert, David B. Lerman; (ii) a Declaration by Vikas Tandon; (iii) deposition testimony from James (Jim) Wolff and Adam Rosen taken in the OBOT IIlawsuit; and (iv) the letters from the Utah “Carbon Counties” previously submitted to the Court in the chapter 11 bankruptcy case. In response, Defendant argues that (a) Plaintiff’s expert report was procedurally deficient; (b) the Tandon Declaration lacked proper foundation and contained inadmissible hearsay; (c) prior depositions of Wolff and Rosen should not be used because they come from a different case and are hearsay; and (d) the letters from the Utah Carbon Counties are not authenticated and are hearsay. Defendant’s objections, however, are without merit.

As to the expert reports, Lerman submitted a sworn and authenticated declaration for the reports satisfying the requirements of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(c)(4), which is applicable through Federal Rule of Bankruptcy Procedure 56. It is immaterial that this sworn declaration was not included when any of these expert reports were initially introduced. Rawers v. United States, 488 F. Supp. 3d 1059, 1105 (D.N.M. 2020) (“Even if a party initially submits an unsworn affidavit or declaration to substantiate a claim under rule 56, if a party attaches an unsworn expert report along with an expert’s sworn declaration or deposition affirming the report, the unsworn report’s deficiencies are cured.”) The reports—which Defendant questioned Lerman about during his deposition—are, therefore, properly before the Court and admissible for summary judgment purposes.

The Tandon Declaration is based on Tandon’s personal knowledge, supported by business records and conversations within the scope of Federal Rule of Evidence 803, and provides sufficient foundation under Federal Rule of Evidence 901—Tandon is the manager of AWL and, pursuant to his declaration, was personally engaged in the activities identified in his declaration. Rule 56 permits reliance on evidence that can be presented in admissible form at trial. Americredit Fin. Servs. v. Lyons, No. 3:19-cv-01045, 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 6782, at *24-25 (M.D. Tenn. Jan. 13, 2022) (“It is fundamental that a declaration, though an ‘out-of-court statement’ that is invariably offered for the truth of every assertion the declarant makes in (or via) the declaration, typically is not excluded from consideration on a motion for summary judgment on the grounds of hearsay…. ‘as long as the proponent of the evidence can proffer that it will be produced in an admissible form ….’” (citation omitted). The declaration is, therefore, admissible.

Both the Wolff Deposition and Rosen Deposition were taken in OBOT II where Defendant was a party, represented by counsel, and had full opportunity to examine the witnesses at the depositions. (Declaration of Skyler M. Sanders in Support of Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment [Doc. 130-1] [“Sanders Decl. III”], Exs. 1–5.) Under Rule 32(a)(8) of the Federal Rule

of Civil Procedure, prior depositions may be used where there are substantial identity of issues and the presence of the adversary party. See Archey v. AT&T Mobility Servs. LLC, No. 17-91-DLB- CJS, 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 53637, at *14, 2019 WL 1434654 (E.D. Ky. Mar. 29, 2019) (“[A]

deposition taken in a different case may be admitted as a sworn statement or affidavit pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(c)(4).”). Defendant itself relies on this testimony in OBOT II, as well as in its opposition to the ITS Motion, further confirming its reliability. (City Obj. [Doc. 123] at ¶ 62.) Additionally, the witnesses reside more than 100 miles from the Court, satisfying Rule 32(a)(4), and the testimony qualifies for a hearsay exception under Federal Rule of Evidence

807. (Sanders Decl. III.); see also S.C. v. Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Inc., No. 1:23-cv-00871, 2024 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35791, at *3, 2024 WL 884672 (N.D. Ohio Mar. 1, 2024). Both the Wolff

Deposition and the Rosen Deposition are, therefore, admissible.

With respect to RJN Exhibit 4, as set forth above, the Court may take judicial notice of its own records, and it does so here. See Fed. R. Evid. 201. Defendant’s argument that RJN Exhibit 4 cannot be relied upon by the Court because it is not authenticated and contains inadmissible hearsay is incorrect. The relevant portions of RJN Exhibit 4 are four letters from the Utah Carbon Counties—Carbon, Sanpete, Sevier, and Emery—on letterhead from each respective county, contain the logo of each respective county, and are signed by the commissioner of each respective county. Under Federal Rule of Evidence 902(7), the letters are self-authenticating. Additionally, the letters are public records setting forth the respective counties’ activities—in this case supporting the Terminal and acknowledging the continuing availability of funds set aside by the counties for the Terminal—thereby qualifying for the Federal Rule of Evidence 803(8) hearsay exception. Defendant does not set forth any circumstances that would indicate a lack of trustworthiness, therefore RJN Exhibit 4 is admissible.

Thus, the Court overrules Defendant’s evidence objections in their entirety. The challenged evidence is admitted and will be considered in ruling on the ITS Motion.

III.DenialofITS’sMotionforSummaryJudgmentisNotWarrantedBecausetheCourtMaintains“RelatedTo”Subject-MatterJurisdictionUnder28U.S.C.§1334(b)

The City re-litigates the arguments previously asserted in its motion to dismiss, which this Court denied on November 21, 2024 (seeDismissal Order) that this adversary proceeding falls outside the broad scope of the district court’s bankruptcy jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1334(b). The City’s arguments remain unpersuasive for the reasons set forth in the Dismissal Order, which are materially restated below for convenience.

It is well established that a bankruptcy court’s subject matter jurisdiction derives from 28

U.S.C. § 1334. In re Resorts Int’l., Inc., 372 F.3d 154, 161 (3d Cir. 2004). Section 1334(b) provides, in relevant part, that “the district courts shall have original but not exclusive jurisdiction of all civil proceedings arising under title 11 or arising in or related to cases under title 11.” See 28

U.S.C. § 1334(b). This adversary proceeding and the allegations and claims set forth herein are “related to” the chapter 11 case.

The Sixth Circuit adopts the Third Circuit’s test in Pacor, Inv. v. Higgins (In re Pacor), 743 F.2d 984 (3d Cir. 1984) for evaluating “related to” jurisdiction over an adversary proceeding. Under Pacor, an adversary proceeding is related to bankruptcy where “the outcome of that proceeding could conceivably have any effect on the estate being administered in bankruptcy. An action is related to bankruptcy if the outcome could alter the debtor’s rights, liabilities, options, or freedom of action (either positively or negatively) and which in any way impacts upon the handling and administration of the bankrupt estate.” Mich. Employment Security Comm. v. Wolverine Radio Co., Inc. (In re Wolverine Radio Co.), 930 F.2d 1132, 1142 (6th Cir. 1991) (quoting Pacor, 743 F.2d at 994) (emphasis in the original). To determine whether a matter is within a bankruptcy court’s jurisdiction, “it is necessary only to determine a matter is at least “related to” the bankruptcy. Wolverine Radio Co., 930 F.2d at 1141.

Relying on the factor-driven analysis from a bankruptcy court opinion from the Eastern District of Kentucky in Tew v. ED&F Man Capital Markets, Ltd. (In re Tew), No. 20-51078, 2023 WL 7981684, at *7 (Bankr. E.D. Ky. Nov. 16, 2023), the City argues that the Court lacks jurisdiction because (a) the City did not actively participate in the chapter 11 case, (b) the subject claims are not rooted in bankruptcy and lack a close nexus with the chapter 11 case, (c) the Debtor

could have brought these claims as part of the chapter 11 case, and (d) the Plan does not adequately preserve jurisdiction over the subject claims. The City is wrong on all counts.

Based on the analysis below, the Court determines that the matters asserted in the Complaint are related to this bankruptcy case and are relevant to the execution of the Plan and Confirmation Order. The Complaint’s allegations are inextricably intertwined with the Debtor’s chapter 11 case and the substantive activity contemplated in the Plan. That is to say, “the outcome of [this adversary] proceeding could conceivably have an effect on the estate being administered in bankruptcy . . . ” as required under Wolverine Radio’smeasurement for related to jurisdiction. Wolverine Radio Co., 930 F.2d at 1142.

A.The CityActively Participated in the Bankruptcy Case When It Objected to theAssumption of the Sublease and Confirmation of the Plan.

The City’s suggestion that it did not actively participate in the Debtor’s chapter 11 case is belied by the facts here. When AWL pursued confirmation of a chapter 11 plan in order to—in the City’s own words—“preserve their value in a [Sublease],” the City actively intervened to prevent the confirmation of both AWL’s and the Debtor’s proposed chapter 11 plans by filing a robust and well-briefed twelve-page objection for the most important stage of the bankruptcy case.2 That action reflects that the City was an active participating party-in-interest in the case, and proves that the Debtor’s and AWL’s preservation of the “value in [the] Sublease” was critical.

B.The Complaint is “Rooted” in the City’s Actions that Lead to ITS’s Bankruptcy and Continue Unabated.

By relying on Tew, the City argues that the Complaint does not “pertain to activity in or

leading to the bankruptcy case” or that there is not a “close nexus between [the Plan] or [this]

2 See the City’s Confirmation Objection (arguing, among other things, that both AWL’s and the Debtor’s proposed plans were “unfeasible” and that the Debtors’ plan was proposed in bad faith); see also Declaration of Bijal Patel[Main Case Doc. 277] and a Request for Judicial Notice [Main Case Doc. 278].

bankruptcy case and the [Complaint] . . . .” Tew, 2023 WL 7981684, *9 (emphasis added). Yet ITS’s purpose—both before bankruptcy and after confirmation—was always to maximize the value of the Sublease. Aptly, in its Complaint, Plaintiff alleges that the City thwarted ITS’s prepetition efforts to raise financing and subsequently monetize the Sublease, and the City continues to interfere with ITS’s post-confirmation efforts to get the benefit of its bargain under the Plan, which is the ability to monetize the assumed Sublease.

The City, like other stakeholders in this bankruptcy case, was aware that the City’s alleged wrongful termination of OBOT’s Ground Lease helped force ITS into chapter 11, and that the evolution of this dispute would ultimately determine ITS’s fate and whether it could confirm and implement a chapter 11 plan. Unlike the Tewdebtor, the Complaint here concerns a pattern of alleged behavior that not only pre-dated ITS’s bankruptcy filing but caused the filing and continued unabated post-confirmation to today.3 Additionally, ITS forewarned the Court that if the Oakland Overburden could not be resolved through cooperation with the City, that ITS would likely be back in front of the Court to adjudicate the issues, which is precisely where the parties find themselves at present. (See, e.g., Debtor’s Obj. to AWL’s Motion to Dismiss [Main Case Doc. 61] at ¶ 35.)

Finally, the City itself highlights its own strong connections not only to ITS and its financial health, but to the bankruptcy case and the success of the proposed reorganization under the Plan. (SeeConfirmation Obj. § I (stating that the City is an “[i]nterested [p]arty” and the “owner of the land … that is the subject of competing plans filed by the Debtors and AWL . . . ”).

3 The City also argues that any proceeds recovered in the adversary proceeding would not “impact the estate” or “be used to pay creditors under the Plan ”As the Tew court notes, however, such factors are not dispositive. Moreover, funds recovered would reimburse the plan proponent

entity that funded the payments made to creditors with allowed claims under the Plan.

C.ITS is a Single-Purpose Entity and Reorganized to Preserve the Value of its Critical Material Asset: the Sublease.

ITS was not a typical chapter 11 debtor and is not a typical reorganized debtor. ITS was a single-purpose entity created to develop the Terminal pursuant to the Sublease. As stated in the Confirmation Objection, the Disclosure Statement, and other chapter 11 filings, ITS’s primary asset was the Sublease. (See, e.g., Disclosure Statement Art. III. A; Confirmation Obj. § I.) ITS’s “reorganization” was subject to several interrelated contingencies, including various pending and potential litigations, that could take years to finally determine, as the Debtor’s Complaint alleges. (SeeConfirmation Obj. § I, II.D-E, III.A.) Unlike the debtor in Tew, ITS was not simply “reentering the market” as a clean new entity with an operating business. Rather, this chapter 11 case—through the confirmed Plan—created a path for ITS to potentially realize the value of the Sublease. (SeeDisclosure Statement § III.C.)

ITS has asserted without meaningful rebuttal that this adversary proceeding is the Debtor’s current best effort to travel that path to monetize the Sublease and implement the Plan’s contemplated reorganization. ITS’s chapter 11 bankruptcy case remains pending; it has not been closed and no final decree has been entered by this Court.

D.ThePlanAdequatelyPreservedJurisdiction.

Although the chapter 11 case was initiated in 2019 and the Plan confirmed in 2020, Debtor’s case remains active before this Court and this Court has continuing jurisdiction over the matter. A review of the Plan and the Confirmation Order sets forth the terms of this Court’s post- confirmation jurisdiction. Specifically, Article IX(A.) provides in relevant part that:

Notwithstanding the entry of the Confirmation Order and the occurrence of the Effective Date, the Bankruptcy Court shall retain non-exclusive jurisdiction of all matters arising out of, and related to, the Chapter 11 Case and the Plan, including jurisdiction to: . . . [1] resolve any matters related to . . . Unexpired Leases . . . [5] issue and implement orders in aid of execution, implementation, or consummation

of the Plan . . . [8] hear and determine disputes arising in connection with the interpretation, implementation, or enforcement of this Plan or the Confirmation Order, including disputes arising under agreements, documents, or instruments executed in connection with this Plan and disputes arising in connection with any Person or entity’s obligations incurred in connection with the Plan . . . [12] hear any other matter not inconsistent with the Bankruptcy Code . . . . [15] enforce all orders previously entered by the Bankruptcy Court.

After the Effective Date, the Bankruptcy Court shall retain jurisdiction with respect to each of the foregoing items and all other matters that were subject to its jurisdiction prior to the Confirmation Date . . . .

(See Plan [Main Case Doc. 245-1] at Article IX(A.); see also Conf. Order [Main Case Doc. 379]

¶ 27.) Notably, the City’s Objection failed to object to these confirmed post-confirmation jurisdiction provisions.

While the Plan does not specify each potential claim and potential litigation target, that lack of minute detail is not problematic. See, e.g., Gordon Sel-Way, Inv. v. U.S. (In re Gordon Sel- Way, Inc.), 270 F.3d 280, 288–89 (6th Cir. 2001). Prepetition and preconfirmation, ITS was a largely underfunded single-purpose entity with few employees and no operations. When AWL and new management assumed control over ITS, it is not surprising that AWL’s Disclosure Statement and the Plan did not identify claims with granular detail, but instead reasonably and adequately identified (i) the kinds of claims that would be preserved (i.e., the “Litigation Claims” that were retained and reserved for prosecution by ITS, as a representative of the Estate in accordance with Bankruptcy Code § 1123(b)(3)(B) pursuant to Article VII.K of the Plan) and (ii) the kinds of disputes over which this Court would retain jurisdiction, including disputes within the categories identified in Article IX.A of the Plan. To expect a non-debtor competing plan proponent such as AWL to know and possess the ability to articulate all claims and disputes with absolute precision is neither practical nor required under the law.The primary question for the Court to answer is whether information both within and beyond the case is sufficient to put a creditor on notice of

potential debtor claims. Nestlé Waters N. Am., Inc. v. Mt. Glacier LLC(In re Mt. Glacier LLC), 877 F.3d 246, 249 (6th Cir. 2017). The answer here is, yes.

Moreover, the Plan’s description of claims and disputes is a far cry from an ambush on an unsuspecting party in interest. The City’s own filings evidence that the City knew that its conduct was central to ITS’s bankruptcy filing and implementation of the Plan.4 From the onset, the Debtor espoused the problems created by the City’s conduct, which was aptly acknowledged and monikered by the Court as the “Oakland Overburden.” (See, e.g., Debtor’s Obj. to AWL’s Motion to Dismiss [Main Case Doc. 61] at ¶ 35.) In this regard, the Debtor specifically asserted early on to the Court that:

The Debtors believe that, with sufficient time in these Chapter 11 Cases, they can negotiate resolutions [concerning the Oakland Overburden] with the City of Oakland that will allow the Project to move forward and enhance the value of the Sublease for the benefit of the Debtors’ creditors. However, if the Debtors cannot consensually remediate the Oakland Overburden by collaborating and partnering with the City of Oakland, then the Debtors further assert that this Court is or can be empowered [to] adjudicate or otherwise address the West Gateway Master Development Agreement dispute, which directly affects the [Sublease] that stems from the Agreement, along with any other Oakland Overburden issues.

(Id. at ¶ 35 (emphasis added).)

The City chose not to challenge the Plan’s broad retention of claims and jurisdiction, despite the fact that the City capably (albeit unsuccessfully) analyzed and attacked other specific aspects of the proposed chapter 11 plans and was, or should have been, aware of Plaintiff’s statements that “this Court is or can be empowered [to] adjudicate” issues with the City.

4 See City Confirmation Obj. ¶ E (stating that “[a]ccording to AWL’s Plan, ‘[t]he Sublease is the Debtor’s primary asset and, upon information and belief, the Debtor has yet to commence development of the Premises nor is such development expected to commence in the near term.’ AWL believes that, under new management, the Reorganized Debtor ‘can successfully develop or actively market and sell the Sublease.’”) (internal citations omitted).

IV.Plaintiff’sClaimsAreNotBarredbyClaimPreclusion

“Claim preclusion arises if a second suit involves (1) the same cause of action (2) between the same parties (3) after a final judgment on the merits in the first suit.” Oakland Bulk & OversizedTerminal, LLC, 112 Cal. App.5th at 559 (citation modified); see also Sanders Confectionery Prods.

v. Heller Fin., Inc., 973 F.2d 474, 480 (6th Cir. 1992). None of these elements are satisfied here.

As to the first element of claims preclusion, the causes of action are different. To determine

whether the causes of action in this matter are the same causes of action brought in OBOT II, the Court focuses on well-documented procedural history. A review of the original complaint demonstrates that OBOT’s causes of action for interference with a prospective economic advantage are not the same as Plaintiff’s causes of action at issue in this matter. (SeeDeclaration of City of Oakland Assistant City Administrator Elizabeth Lake [Doc. 118-1], Ex. L.) Indeed, the tort claims in OBOT IIrelated to Plaintiff involve “the future economic benefit” OBOT would receive through the Sublease (i.e.,rent payments). In contrast, Plaintiff’s claims in this matter relate to Defendant interfering with Plaintiff’s financing and ability to develop the Terminal resulting in Plaintiff’s bankruptcy and the damage to Plaintiff when AWL assumed the Sublease through the confirmed plan. (SeeCompl. ¶ 62.)

More importantly, claim preclusion does not apply where the second lawsuit involves different causes of action, successive breaches, or is based on rights that accrued after the earlier judgment. Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC, 112 Cal. App. 5th at 559 (citing 7 Witkin, Cal. Procedure (6th ed. 2025) Judgment, § 433). Claim preclusion “extends only to the facts in issue as they existed at the time the judgment was rendered and does not prevent a reexamination of the same questions between the same parties where in the interim the facts have changed or new facts have occurred which may alter the legal rights of the parties.” City of Oakland v. Oakland Police & Fire Retirement Sys., 224 Cal. App. 4th 210, 230 (Cal. Ct. App. 2014). Here, Plaintiff

did not file its petition for chapter 11 bankruptcy until after OBOT filed its original complaint, and

the amended complaint in OBOT II did not seek to recover the damages Plaintiff realized through the Sublease’s assumption by AWL for approximately $20 million. Moreover, Defendant’s tortious conduct in preventing the development of the Terminal continues to this day, with the new Mayor of Oakland and others standing resolute against the development of a coal terminal, thereby resulting in successive tortious conduct not covered under the doctrine of claim preclusion. In short, this dispute is on-going and was not resolved by OBOT II.

Defendant’s primary right argument does not save the theory. “It is true that when two actions involving the same parties seek compensation for the same harm, they generally involve the same primary right. But, not always: Different primary rights may be violated by the same wrongful conduct.” Ivanoff v. Bank of Am., N.A., 9 Cal. App. 5th 719, 728 (Cal. Ct. App. 2017) (citation modified). Although the OBOT IIamended complaint and Plaintiff’s complaint in this adversary proceeding share many of the same underlying facts, Plaintiff’s adversary complaint seeks redress for a different harm under a different contract. OBOT’s complaint concerned breach of the Ground Lease (the issue finally adjudicated by the California courts), while Plaintiff’s adversary complaint is about Defendant’s tortious conduct regarding the Sublease and associated financing, thereby leading to Plaintiff’s bankruptcy, and Defendant’s continuing bad faith conduct in taking any steps necessary to block development of the Terminal. “Thus, because breaching a contract inflicts harm on a legally protected interest different from tortious conduct … two different primary rights arise.” Fujifilm Corp. v. Yang, 223 Cal. App. 4th 326, 332 (Cal. Ct. App. 2014); see also Scripps Clinic v. Superior Court, 108 Cal. App. 4th 917, 928 (Cal. Ct. App. 2003) (citation modified) (finding that the plaintiffs state two distinct causes of action for interference

with contract when they alleged that the defendants wrongfully interfered with two separate contracts). For these reasons, the causes of action are distinct.

As to the second element of claim preclusion, the Court similarly finds that the parties are

different from OBOT II. Defendant argues that, because Plaintiff was in “privity” with OBOT, Plaintiff is precluded here. But “[a] nonparty alleged to be in privity must have an interest so similar to the party’s interest that the party acted as the nonparty’s ‘virtual representative’ in the first action.” Castillo v. Glenair, Inc., 23 Cal. App. 5th 262, 276–277 (Cal. Ct. App. 2018). “If the interests of the parties in question are likely to have been divergent, one does not infer adequate representation and there is no privity. If the party’s motive for asserting a common interest is relatively weak, one does not infer adequate representation and there is no privity.” Gottlieb v. Kest, 141 Cal. App. 4th 110, 150 (Cal. Ct. App. 2006). “The determination of privity depends upon the fairness of binding a party with the result obtained in earlier proceedings in which it did not participate. Whether someone is in privity with the actual parties requires close examination of the circumstances of each case.” Planning & Conservation League v. Castaic Lake Water Agency, 180 Cal. App. 4th 210, 229–30 (2009) (citation modified).

Here, the interests of OBOT and Plaintiff were not so aligned that OBOT was a “virtual representative” of Plaintiff in the OBOT IIlawsuit. OBOT IIinvolved Defendant’s breach of the Ground Lease. Because Plaintiff is not a party to the Ground Lease, Plaintiff would not have any claims against Defendant being pursued by OBOT. Instead, as the Court previously recognized, the claims now asserted by Plaintiff are distinct from OBOT’s and involve Plaintiff’s own direct harm: “The Complaint seeks to hold Defendant accountable for its interference with Plaintiff’s third-party contract and prospective economic advantage and the damages directly resulting therefrom.” (Dismissal Order at 6.) More, neither Plaintiff nor OBOT control one another.

Compare Sanders Confectionery Prods., 973 F.2d at 481 (finding privity where the plaintiffs were the president and chairpersons of each company and had the ability to control the decision of each company). In fact, notably, these entities were adverse to each other during the main bankruptcy case. (See, e.g., OBOT Objections to Plan and Plan Supplement [Main Case Docs. 280-81]; OBOT Motion for Relief from Stay [Main Case Doc. 304]; OBOT Objection to Debtor’s Motion to Assume Sublease [Main Case Doc. 309].)

To address Defendant’s claim that Plaintiff is in privity with OBOT because Plaintiff paid a portion of the OBOT IIlegal fees, those costs were forced upon Plaintiff as part of its rent obligation under the Sublease. Specifically, the obligation to pay the proportionate OBOT II legal fees is contained in Section 2.10.1 of the Sublease, which is a sub-section of Section 2.10 (Additional Rent). If Plaintiff did not make this Additional Rent payment, it would have been in default of the Sublease. The circumstances demonstrate that OBOT’s and Plaintiff’s interests diverged such that it would not be fair to hold Plaintiff in privity with OBOT for purposes of preclusion.

As to the third element of claim preclusion, there is no final judgment on the merits related

to the tort claims in OBOT II. OBOT voluntarily omitted all tort claims from its amended complaint in OBOT II after the California court gave OBOT leave to amend the pleadings. “By definition, a voluntary dismissal without prejudice is not a final judgment on the merits.” Syufy Enter. v. City of Oakland, 104 Cal. App.4th 869, 879 (Cal. Ct. App. 2002); see also CFE Grp., LLC v. FirstMerit Bank, N.A., 809 F.3d 346, 351 (7th Cir. 2015). That is what happened here. OBOT voluntarily dropped its tort claims when granted leave to amend, which cannot operate as a final judgment of OBOT’s tort claims, let alone preclusion that extends to a third-party bringing different tort claims. “Other examples of judgments that are not on the merits include the following: a judgment on

statute of limitations grounds.” Association of Irritated Residents v. Department of Conservation, 11 Cal. App. 5th 1202, 1220 (Cal. Ct. App. 2017). Thus, because no tort claims were adjudicated by the California courts and made final through judgment, the third element of claim preclusion fails and Defendant’s motion should be denied for the same.

Because each of these required elements for claim preclusion is lacking, the Court concludes that Plaintiff’s claims are not barred.

V.Plaintiff’sClaimsAreNotBarredbytheStatuteofLimitations

Defendant argues Plaintiff’s claims are time-barred because the statute of limitations began to run when Plaintiff allegedly became aware of Defendant’s tortious conduct. Not so. “Under an estoppel theory, the focus is on the defendant’s conduct which induced the plaintiff to forbear legal action, not on what the defendant subjectively believed.” National Railroad Passenger Corp. v. Crown-Trygg Corp., 170 Ill. App. 3d 946, 952, 524 N.E.2d 954 (Ill. App. Ct. 1988). As this Court has already acknowledged, Plaintiff’s claims did not become ripe until the finding in OBOT II that Defendant wrongfully attempted to terminate the Ground Lease and that Defendant acted in bad faith in failing to “substantively respond to any of the correspondence, materials or issues raised by OBOT, Plaintiff or Millcreek Engineering since September 22, 2018 . . . .” (Statement of Decision at 85:22–27; Dismissal Order at 16–18.) Therefore, Plaintiff’s claims did not ripen until at least November 22, 2023, and, consequently, are not barred. Moreover, in light of Mayor Barbara Lee’s 2025 statements that she will do everything in her power to stop the Terminal from being constructed, the tortious conduct of Defendant continues to present.

The undisputed evidence in this adversary proceeding confirms that Plaintiff’s causes of action are not time-barred for the reasons set forth in this Court’s prior Dismissal Order, which are materially restated below for convenience.

The City argues Plaintiff’s pair of tort claims are barred by a two-year statute of limitations applicable to tort claims against government entities as set forth in Section 945.6 of the California Government Code (“Gov. Code”). This argument, however, is incorrect. Gov. Code § 945.6

provides that, for purposes of computing the time in Gov. Code § 945.6, “the date of accrual of a cause of action … is the date upon which the cause of action would be deemed to have accrued within the meaning of the statute of limitation which would be applicable thereto if there were no requirement that a claim be presented ” Gov. Code, § 901; see also City of Pasadena v. Superior

Court, 12 Cal. App. 5th 1340, 1349 (Cal. Ct. App. 2017). Thus, the issue is when did Plaintiff’s claims against the City become actionable? The City provides the answer in its previous filings with this Court: not until conclusion of the OBOT IIlawsuit.

The City represented to this Court that ITS had no rights or claims related to the Sublease until OBOT II was resolved: “There can be no dispute that the termination of the Ground Lease is the subject of active litigation. If the California court determines that the Ground Lease was, in fact, terminated in 2018, there is nothing left for the plan proponents to assume.” (SeeCity Confirmation Objection at 12.) Put differently, if the outcome of OBOT IIwas a ruling that the Ground Lease was unlawfully terminated by the City in 2018—which is what happened—then the City could be held liable for refusing to acknowledge the assumed Sublease, issue the estoppel and non-disturbance agreement, and process ITS’s permits. Consequently, the City is judicially estopped from now reversing field and contradicting its prior representations to this Court. New Hampshire v. Maine, 532 U.S. 742, 749 (2001); Dot ConnectAfrica Trust v. Internet Corp. for Assigned Names & Numbers, 68 Cal. App. 5th 1141, 1158 (Cal. Ct. App. 2021).

Because the City’s bad faith conduct and breach of the Ground Lease remained unclear until the Statement of Decision was issued in November 2023, Plaintiff did not have sufficient

knowledge as to whether it would have any claim against the City until OBOT II was resolved. See April Enterprises, Inc. v. KTTV, 147 Cal. App. 3d 805, 832 (Cal. Ct. App. 1983) (holding that the discovery rule applies where breaches “can be, and are, committed in secret and, moreover, where the harm flowing from those breaches will not be reasonably discoverable by plaintiffs until a future time”); Brown v. Ferro Corp., 763 F.2d 798, 801 (6th Cir. 1985) (noting that a ripeness analysis includes a discretionary determination beyond the Article III standing considerations). Once OBOT II was concluded, Plaintiff brought this action within the two-year statute of limitation period.

The City’s petition to the California Supreme Court for re-review of the Judicial Decisions provides no basis for dismissal of Plaintiff’s claims. First, on September 17, 2025, the City’s

petition for review was denied by the California Supreme Court. Second, under California law,

perfecting an appeal only stays proceedings in the trial court regarding the order or judgment appealed, including enforcement of the same. California Code of Civil Procedure sections 916 et seq. Thus, Plaintiff’s claims are not barred by the statute of limitations.

VI.Plaintiff’sClaimsAreNotBarredbytheGovernmentClaimsAct

A primary argument advanced by the City (both in its motion to dismiss and in its motion for summary judgment) as to why ITS’s claims should be dismissed is that California’s Government Claims Act (Government Code § 810, et seq.) makes the City immune to liability. The Government Claims Act “establishes the basic rules that public entities are immune from liability except as provided by statute (§ 815, subd. (a)), that public employees are liable for their torts except as otherwise provided by statute (§ 820, subd. (a)), that public entities are vicariously liable for the torts of their employees (§ 815.2, subd. (a)), and that public entities are immune where their employees are immune, except as otherwise provided by statute (§ 815.2, subd. (b)).”

Caldwell v. Montoya, 10 Cal. 4th 972, 980, 897 P.2d 1320 (1995). The City bases its immunity claim on section 820.2, which establishes traditional immunity for discretionary acts. Section

820.2 states that “[e]xcept as otherwise provided by statute, a public employee is not liable for an injury resulting from his act or omission where the act or omission was the result of the exercise of the discretion vested in him, whether or not such discretion be abused.”

Before the Government Claims Act was enacted in 1963, liability of public entities in tort turned on whether the conduct arose from governmental or proprietary activities. See Sanders v. City of Long Beach, 54 Cal. App. 2d 651, 657–58, 129 P.2d 511 (1942) (“[S]ince the evidence is prima facie sufficient to establish negligence on private proprietary standards, the question of notice to a responsible officer of defendant city, such as would be required to meet the conditions of the Public Liability Act, becomes immaterial.”) Sovereign immunity barred liability for governmental functions. See Gates v. Superior Court, 32 Cal. App. 4th 481, 497–501 (Cal. Ct. App. 1995) (reviewing in detail the development of the Government Claims Act). Such functions included enforcing police regulations, preventing crime, protecting public health, fighting fires, caring for the poor, and educating children, along with the buildings and equipment used for those purposes. Sanders, 54 Cal. App. 2d at 658–59. By contrast, when the conduct involved proprietary activities, public entities were subject to the same liability as private employers or property owners for employee negligence or unsafe property conditions. Gates, 32 Cal. App. 4th at 497. When the Government Claims Act was enacted, however, it did not include an express “governmental vs. proprietary activity” distinction for application of the Government Claims Act.

Following the enactment of the Government Claims Act, some cases have cited Cabell v. State of California, 67 Cal.2d 150 (Cal. 1967), to argue that there is no distinction between governmental and proprietary activities in tort liability cases. In Cabell, court found that the state

had immunity for discretionary decisions regarding design and construction of the bathroom, to argue that the distinction between proprietary vs. governmental capacity is no longer a consideration in Government Claims Act cases. Id. at 151–53. But Cabellwas (i) predicated on Government Code section 830.6, which expressly states that a public entity is not liable for the plan or design of public buildings, and (ii) still acknowledged that “public entities liable for injuries caused by arbitrary abuses of discretion[ ]….” Id. at 151–53. See also Slapin v. Los Angeles International Airport, 65 Cal. App. 3d 484, 490–91 (Cal. Ct. App. 1976) (concluding that imposing liability for inadequate lighting in a parking lot would not interfere with the public entity’s discretionary decision-making regarding the level of policing at that location). Courts have made clear that ministerial acts “that merely implement a basic policy already formulated” are not protected by immunity. Caldwell, 10 Cal. 4th at 976, 981. Immunity extends only to “deliberate and considered policy decisions” reflecting a conscious weighing of risks and benefits. Id. It makes no difference that an employee usually performs discretionary functions “if, in a given case, the employee did not render a considered decision.” Id.

The California Supreme Court has repeatedly distinguished between policy decisions and operational acts. For example, it has denied immunity for a bus driver’s failure to intervene in a passenger assault (Lopez v. Southern Cal. Rapid Transit Dist., 40 Cal.3d 780, 793–95 (Cal. 1985)); a college district’s failure to warn of known crime risks in a student parking lot (Peterson v. San Francisco Community College Dist., 36 Cal.3d 799, 815 (Cal. 1984)); libelous statements by a county clerk during a press interview about official matters (Sanborn v. Chronicle Pub. Co., 18 Cal.3d 406, 415–16 (Cal. 1976)); university therapists’ failure to warn a foreseeable homicide victim of prior threats (Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, 17 Cal.3d 425, 444–47 (Cal. 1976)); and a police officer’s negligent handling of a traffic investigation once commenced

(McCorkle v. City of Los Angeles, 70 Cal.2d 252, 261–62 (Cal. 1969)). These and similar cases underscore that, under the Government Claims Act, courts must determine whether the challenged conduct involves discretionary governmental decisions or ministerial acts.

In the Court’s evaluation of Plaintiff’s tortious interference claims, nothing in the record before the Court supports a claim that Defendant’s actions at issue in this matter involved discretionary government decisions. To the contrary, Defendant’s conduct goes beyond a mere abuse of discretion to tortious acts intended to interfere with Plaintiff’s ability to construct and operate the Terminal.

The City, places heavy emphasis upon Yee v. Superior Court, 31 Cal. App. 5th 26 (Cal. Ct. App. 2019), to argue that it cannot be liable to ITS for (i) refusing to recognize the Sublease or execute a non-disturbance agreement based on its decision to terminate the Ground Lease, (ii) stating in the estoppel certificate that the Ground Lease had been terminated, and (iii) the actions of municipal employees in carrying out those decisions—because the termination of the Ground Lease was a uniquely governmental act that qualifies for immunity. But such position is inconsistent with the holdings reached in Yee. In that case, a complaint for “abuse of process” was filed against the state controller’s office in connection with the state collecting protected documents as part of an unclaimed property audit. Id. at 30. The Yeecourt pointed out, that case was about whether a public entity should be vicariously liable for a tort when “conducting a public function that only the public entity can perform ….” Id. at 34. Only a government entity could (i) conduct an unclaimed property audit and (ii) be sued for abuse of process. Id. at 32–33. Additionally, the Yeecourt emphasized that government tort liability required analysis of “the specific circumstances alleged in a particular case ….” Id. at 39 (emphasis in original). Following

this guidance, the Court concludes that immunity does not apply to the specific circumstances alleged here.

Defendant’s act of entering into a lease (that includes the right to sublease the premises) is not a public function reserved solely to a public entity. Leases are entered into every day by private non-government parties. Similarly, acknowledging a sublease, providing accurate information on an estoppel certificate, and providing a non-disturbance agreement are not specific to a public entity performing a public function—these actions are commonly imposed on private landlords in the ordinary course of business. When not performed, landlords are held liable. See e.g. Linden Partners v. Wilshire Linden Assocs., 62 Cal. App. 4th 508, 522, 524–30 (Cal. Ct. App. 1998) (concluding that a property owner has a duty to include correct information in an estoppel certificate, even where the misrepresentation is based on the property owner’s mistaken belief); CR-RSC Tower I, LLC v. RSC Tower I, LLC, 429 Md. 387, 400–01, 429–32 (2012) (finding that a

landlord’s incorrect representation in an estoppel certificate—that the tenant was in breach of the lease—interfered with the tenant’s financing and holding the landlord liable for the damages caused thereby); Chumash Hill Props., Inc. v. Peram, 39 Cal. App. 4th 1226, 1232 (Cal. Ct. App. 1995) (concluding that it was legally and equitably proper to require a landlord to honor a non- disturbance agreement).

For similar reasons, Defendant’s reliance on Freeny v. City of San Buenaventura, 216 Cal. App. 4th 1333 (Cal. Ct. App. 2013) is misplaced. Specifically, Freeny addressed tort immunity for legislative decision-making, not a municipality’s tortious conduct by a landlord. 216 Cal. App. 4th at 1341–45. (“We conclude that the City Council defendants are immune from tort damages for their legislative denial of plaintiffs’ application.”) The City’s refusal to issue a valid estoppel certificate and enter into a non-disturbance agreement, ignoring financing communications, and

failure to acknowledge the Sublease after it improperly attempted to terminate the Ground Lease is actionable misconduct not protected discretionary policymaking.

The Court’s finding that Defendant can be held liable for tortious interference with a prospective economic advantage and tortious interference with contract is not novel. Other California courts have already reached the same conclusion. City of Costa Mesa v. D’Alessio Investments, LLC, 214 Cal. App. 4th 358, 378 (Cal. Ct. App. 2013) (“It is also possible for a public entity and its employees to be held liable for intentional interference with prospective economic advantage….”); H & M Associates v. City of El Centro, 109 Cal. App. 3d 399, 405–09 (Cal. Ct. App. 1980) (holding that municipalities can be liable for intentional interference with contractual relationships despite the assertion of various immunities and privileges]). Indeed, the Court finds H & M Associatesinstructive. In that case, a city manager’s actions in shutting off water service to the plaintiff’s apartment complex and notifying others of that action—which led to tenant departures, mortgage foreclosure, and loss of the property—were not discretionary and therefore not protected by the immunities afforded to public employees and entities under Government Code sections 815.2 and 820.2. Id. at 406. While a city ordinance granted the manager broad authority as the administrative head of government, it did not classify or describe the conduct at issue as discretionary. Id. As set forth herein, the conduct of Defendant’s employees to interfere with the Sublease and stop the Terminal project is not discretionary decision making, but tortious conduct; as a result, Defendant is vicariously liable for the actions of its employees. Thus, the Court concludes that the Government Claims Act does not bar Plaintiff’s tort causes of action.

VII.Plaintiff’sClaimsareValidontheMeritsandSubstantiatedbyUndisputedEvidence

Having found that Plaintiff’s claims are not precluded by any doctrine or other defense asserted by Defendant, the Court turns to the merits. For the reasons stated below, the Court finds

that Defendant is liable for both tortious interference with prospective economic advantage and tortious interference with contract.

A. Defendant Liable for Tortious Interference with Prospective Economic Advantage.

To establish interference with a prospective economic advantage, the plaintiff must prove

(1) an economic relationship between the plaintiff and some third party, with the probability of future economic benefit to the plaintiff; (2) the defendant’s knowledge of the relationship; (3) intentional acts on the part of the defendant designed to disrupt the relationship; (4) actual disruption of the relationship; and (5) economic harm to the plaintiff proximately caused by the acts of the defendant. Korea Supply Co. v. Lockheed Martin Corp., 63 P.3d 937, 950 (Cal. 2003). Moreover, “interference which makes enjoyment of a contract more expensive or burdensome may be actionable ….” Pacific Gas & Elec. Co. v. Bear Stearns & Co., 50 Cal.3d 1118, 1127 (Cal. 1990).