Oakland (Special to ZennieReport.com) – On Friday, June 29th, in the 1st Appellant District, District Two, Court of Appeal of The State of California, the Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal aka “OBOT” and its Founder California Capital Investment Group Managing Partner Phil Tagami, achieved a milestone win that was as much a giant loss for the City of Oakland. Appellant Court Judge Therese M. Stewart upheld the lower court ruling in favor of Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal, LLC (OBOT) building the planned bulk terminal, the award totally $6.8 million, and the ability to transport a number of minerals, including iron ore and coal.

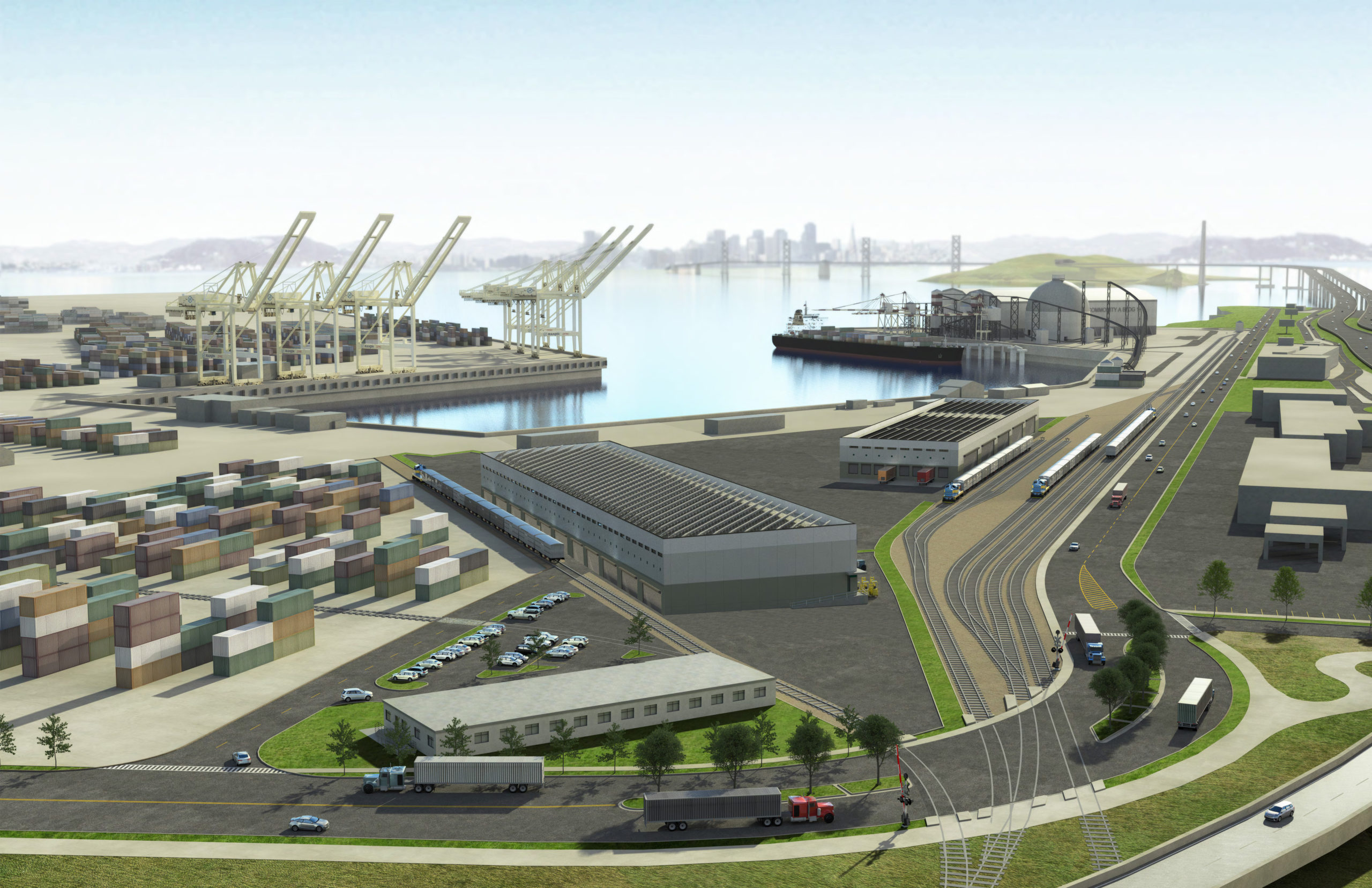

It’s important to remind all that this project concept, which is not a coal terminal, was a favorite of Oakland: Sharing The Vision in 1991:

It’s also important to note that the City of Oakland helped identify coal as a commodity to transport, and hired The Tioga Group to evaluate Phil Tagami’s team’s ability to develop the facility. See “The Oakland Coal Truth: Behind The Coverup Of OBOT And Coal By The City Of Oakland” over here at ZennieReport.com.

The City of Oakland (usually the City, sometimes Oakland) entered into a series of agreements with Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal, LLC (OBOT) that gave OBOT the right to develop a bulk cargo shipping terminal at the site of the former Oakland Army Base. One of the agreements was OBOT’s “Ground Lease” of property at the project site for a term of 66 years.

But amid public backlash after word spread that coal might be transported through the terminal, the City moved to block coal there. Since then, the parties have been embroiled in extensive litigation—and three appeals, one in federal court, two here.

The dispute here arose when the City terminated OBOT’s Ground Lease assertedly because OBOT failed to meet the “Initial Milestone Date,” the date by which it was required to commence and/or complete certain aspects of the construction of the project.

OBOT Sues City of Oakland For Breach Of The Ground Lease

Following that termination, OBOT and its subtenant, Oakland Global Rail Enterprise (OGRE) (when referred to collectively, plaintiffs), sued the City, the operative complaint asserting causes of action for breach of the Ground Lease, breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing, and declaratory relief.

Plaintiffs alleged that OBOT made efforts to advance the project, but that the City refused to cooperate and fulfill its own obligations, making OBOT’s progress impossible; that the City’s actions triggered a force majeure provision in the

Ground Lease, the effect of which excused OBOT’s failure to meet the Initial Milestone Date and entitled OBOT to an extension to perform; and that by refusing to honor the force majeure provision and instead terminating the Ground Lease, the City breached the Ground Lease.

The City responded, asserting that a judgment in a prior federal action between the parties barred plaintiffs’ claims in this action under the doctrine of res judicata. The City also countersued for breach of contract and declaratory relief, asserting OBOT had itself to blame for missing the Initial Milestone Date.

Following a bifurcated bench trial on the issue of liability, the trial court (the Hon. Noël Wise) issued a 95-page statement of decision finding the City liable on plaintiffs’ claims, and entered judgment for plaintiffs. Then, in separate orders, she awarded plaintiffs attorney fees and costs.

The City appeals from the judgment and the orders asserting four arguments, that Judge Wise: (1) misinterpreted and misapplied the force majeure provision; (2) interpreted the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing to “duplicate or alter” express terms of the Ground Lease; (3) erroneously declined to apply claim preclusion; and (4) improperly entered judgment to OGRE on third party breach of contract claims. We conclude that none of the arguments has merit, and we affirm.

BACKGROUND: The Parties and the Project

Plaintiffs and respondents are OBOT, a real estate investment development firm that is wholly owned by California Capital & Investment Group (CCIG), and OGRE, another wholly owned subsidiary of CCIG and a subtenant of OBOT.1 Defendant and appellant is the City of Oakland.

Beginning in 2010, OBOT and the City entered into a series of agreements for the development of some 34 acres at the site of the former Oakland Army Base in general, and in particular the “West Gateway” portion of the base (project). These agreements came to include a 2013 “Development Agreement” (Development Agreement) and ultimately a 2016 “Ground Lease” (Ground Lease) under which OBOT ground-leased the West Gateway property and the existing rail right of way for a 66-year term.

It was to be a huge project, to include a bulk commodity shipping terminal and associated railway improvements (terminal), which was envisioned as a facility for unloading bulk goods from railcars and transferring those goods onto ships for export to other countries. Each of the agreements was voluminous, 2 and some of their pertinent provisions will be described below. Suffice to say here that the agreements granted OBOT the right to develop, build, and operate the terminal, according to specific required time frames, on the West Gateway property.

To complete the description of the parties, we note this observation by

NOTE: 1 After the Ground Lease was executed, OGRE was formed to develop and operate the rail portions of the project, and OGRE subleased from OBOT the rail right-of-way portion of the premises of the project. 2 For example, the Ground Lease is 146 pages, with exhibits 594 pages.

Judge Wise in her statement of decision3: “[t]he principals of OBOT and OGRE, Mark McClure and Phil Tagami, have a long history of goodwill and public service with the City. Mr. Tagami served on Oakland Planning Commission’s Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board, served as both a commissioner and the president of the Port of Oakland (Port)4 . . . , and led some of the economic revitalization efforts of former City Mayor Elihu Harris.

Mr. McClure served as a Port commissioner from 2006 to 2009. Prior to working on this Project, Messrs. McClure and Tagami, through various business entities, successfully worked on complicated and historic development projects in Oakland . . . .

“Over the years, Messrs. McClure and Tagami cultivated relationships with many people who are or were City employees and leaders . . . . In some instances, these interpersonal roots extend for decades; former Mayor Libby Schaaf has known Messrs. McClure and Tagami since high school.

“This history of public service and successful collaboration informed the City’s decision to select Messrs. Tagami and McClure (through CCIG, OBOT, and OGRE) as the developer for the project and as the City’s representative to manage the Oakland Army Base project’s public infrastructure improvements . . . .

Former Mayor Schaaf testified she had confidence in the City’s selection of OBOT to lead the Project because she had seen Mr. Tagami ‘take on very difficult and complicated development projects and succeed.”

(Fn. and italics omitted.)

As will be seen, the history of cooperation and collaboration would not continue. More like pulling teeth.

Coal, the Ordinance and Resolution, and the Federal Case

After the Development Agreement was signed in 2013, word spread that OBOT was making plans to possibly transport coal through the terminal. This generated public concern—and backlash. Against that background, the City held public hearings, following which in the summer of 2016, the City enacted an ordinance that categorically barred bulk material facilities in Oakland from maintaining, loading, transferring, storing, or handling any coal (ordinance).

The City then adopted a resolution that applied the ordinance specifically to OBOT’s terminal (resolution). This generated the first of the lawsuits between the parties. In December 2016, OBOT filed a lawsuit in federal court, in which OBOT asserted that the City breached the Development Agreement by applying the coal ban to the terminal (federal case).

Following a lengthy bench trial, on May 15, 2018, the district court filed a 24-page published opinion holding for OBOT: Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC v. City of Oakland(N.D.Cal. 2018) 321 F.Supp.3d 986. The district court framed the primary question at issue as “whether the record before the City Council when it made this decision [adopting the resolution] contained substantial evidence that the proposed coal operations would pose a substantial health or safety danger.” (Id.at p. 988.) The district court answered “no,” ruling for OBOT all the way (id.at pp. 988–989), and entered judgment enjoining the City from applying the ordinance to OBOT or restricting future coal operations to the terminal. (Id.at pp. 1010–1011.)5

But the worst was yet to come, when in 2018 the City terminated the Ground Lease assertedly because OBOT failed to meet the “Initial Milestone Date.”

The City Terminates the Ground Lease

By way of background, on February 16, 2016, the parties entered into the Ground Lease that granted OBOT the right to use and operate the West Gateway property and the existing rail right of way for 66 years. The Ground Lease set forth the scope and timing of the project, including two “milestones,” or dates by which to complete significant aspects of construction of the terminal.

As relevant here, the “Initial Milestone Date” was the date by which OBOT had to commence construction of the terminal and at least one of the components of the specified “Minimum Project Rail Improvements.” The Initial Milestone Date was defined as 180 days after the “Commencement Date,” which the Ground Lease identified as February 16, 2016.

The Ground Lease, however, included a provision that stated that dates specified therein “shall be tolled” if certain conditions were met, and at trial the parties stipulated that the Commencement Date was tolled until February 15, 2018. Thus, the Initial Milestone Date was August 14, 2018.

The Ground Lease also imposed obligations on the City. For example, the Ground Lease stated that “the City shall use commercially reasonable efforts to enter into a ‘Rail Access Agreement’ . . . with the Port which shall provide a definitive written agreement regarding (i) the rights of use with respect to the Port Rail Terminal to be reserved in favor of the West

NOTE: 5 The City appealed the judgment, and in May 2020, the Ninth Circuit affirmed. (Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC v. City of Oakland (9th Cir. 2020) 960 F.3d 603.)

Gateway . . . , (ii) the services to be provided by the Port Rail Terminal Operator, and (iii) the parameters for the rates to be charged for such services.” The Ground Lease also stated that the “City shall commence construction of the Funded Public Improvements” as defined therein, “and diligently prosecute the same to Completion.”

Additionally, the Ground Lease included a “force majeure” clause, which provided that a party “whose performance of its obligations hereunder is hindered or affected by events of Force Majeure shall not be considered in breach of or in default in its obligations hereunder to the extent of any delay resulting from Force Majeure,” and that a party may seek an extension of time to perform its obligations with notice to the other party.

The Ground Lease defined “force majeure” as “events which result in delays in Party’s performance of its obligations hereunder due to causes beyond such Party’s control, including, but not restricted to, acts of God or of the public enemy, acts of the government, acts of the other Party . . . .”

As will be discussed below, OBOT made various claims of force majeure, to no avail. And on November 22, 2018, the City terminated the Ground Lease on the basis that OBOT was in default of its obligation to meet the Initial Milestone Date. This lawsuit followed.

The Proceedings Below

The Pleadings, The Anti-SLAPP Motion, And The Appeal

On December 4, 2018, plaintiffs filed in the Alameda County Superior Court a complaint against the City asserting 12 causes of action. On January 14, 2019, the City filed a demurrer, a standard motion to strike the complaint (Code Civ. Proc., § 436), and an anti-SLAPP motion (id., § 425.16).

The trial court (Hon. Jo-Lynne Q. Lee) partly sustained the demurrer with leave to amend and partly granted the motion to strike. As a result, Judge Lee noted, she did not have an operative complaint before her to assess plaintiffs’ causes of action, and so denied the anti-SLAPP motion without prejudice as premature.

Ignoring Judge Lee’s denial as premature, the City immediately appealed the denial of the anti-SLAPP motion, an appeal that, of course, stayed the case—a stay that would put a 17-month halt to OBOT’s lawsuit.

While that appeal was pending, on May 28, 2020, the City filed a separate action in Alameda County Superior Court against OBOT and CCIG asserting claims of breach of contract and declaratory relief.

On September 17, 2020, we filed a published opinion where, reaching the merits of the anti-SLAPP motion on de novo review, we reversed the order denying the City’s motion “without prejudice” and remanded with directions to enter an order denying the motion on the merits: Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC v. City of Oakland(2020) 54 Cal.App.5th 738, 765.6

On December 11, plaintiffs filed a first amended complaint asserting six causes of action: breach of contract (first and second causes of action); anticipatory breach (third cause of action); breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing (fourth cause of action); declaratory relief (fifth cause of action); and specific performance (sixth cause of action). Plaintiffs sought damages, specific performance, and injunctive relief.

As plaintiffs summarized their claims: “Since the issuance of the Federal Ruling in May 2018, the City has resolved to thwart completion of the Project by repudiating its contractual obligations under the Lease and

NOTE: We ended our opinion with six pages of “Closing Observations . . . and a Plea,” the observations criticizing the City’s appeal and its claimed motive for filing it. (Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC v. City of Oakland, supra, 54 Cal.App.5th at pp. 760–765.)

[Development Agreement]. After the federal court enjoined the City from legislating a ban on a legally permissible use of the Terminal, the City breached its material obligations under the Lease and [Development Agreement] and has aggressively taken steps to prevent OBOT’s performance under the Lease and Plaintiffs’ receipt of the benefit of the bargain thereunder.

Such breaches include and are not limited to: repudiation of the Lease; refusal to honor OBOT’s Force Majeure rights under the Lease . . . ; failure and refusal to turn over possession of and provide access to the very premises that Plaintiffs have a right and obligation to occupy and improve; bad faith refusal to address essential prerequisites for completion of the project, including but not limited refusing to turn over to Plaintiffs the Railroad Right of Way; failing to negotiate in good faith and expend commercially reasonable efforts to enter into a Railroad Access Agreement with the Port of Oakland; [and] imposing in bad faith unreasonable and discriminatory obstacles for permit submissions and applications . . . .”

With respect to force majeure, plaintiffs alleged that over the three year period between March 11, 2016 and March 19, 2019, OBOT sent the City multiple notices in which it asserted that the City’s actions constituted force majeure events within the meaning of the Ground Lease, entitling OBOT to an extension of the Commencement Date of the Ground Lease.

Plaintiffs alleged, however, that the City failed to honor OBOT’s rights under the force majeure provision and thus “repudiated the Lease.” On January 11, 2021, the City filed its answer, generally denying the allegations and asserting various affirmative defenses, including res judicata.

On March 19, Judge Wise consolidated plaintiffs’ lawsuit with the City’s countersuit.

The Trial And The Statement Of Decision On Liability

On July 6, 2023, Judge Wise set the matter for a bench trial and bifurcated the issues of liability and remedies. The trial took place over the course of several months, with the liability phase commencing on July 10 and concluding on October 11, the remedies phase concluding on December 1.

During the liability phase, Judge Wise heard extensive testimony from numerous witnesses (including Tagami, McClure, former Mayor Schaaf, and City employees), admitted extensive documentary evidence, and heard hours of argument by counsel. After issuing a tentative proposed statement of decision and considering the City’s objections and plaintiffs’ response, Judge Wise issued a 95-page “[F]inal Statement of Decision as to liability” providing a detailed exposition of her factual and legal findings. Much of what she found and concluded is not germane to the issues presented on appeal. We focus on what is.

Issues Presented and Overview

Judge Wise noted that the parties did not dispute that they entered into the Development Agreement and the Ground Lease; that “they continued to be bound by the terms of” these agreements; and that “August 14, 2018 [was the] Initial Milestone Date as defined in the Ground Lease.” The parties also did not appear to dispute that the City terminated the Ground Lease on

November 22, 2018. Judge Wise also resolved a conflict in the evidence as to whether OBOT met the Initial Milestone Date, concluding that it did not.

As Judge Wise framed it, “[t]he narrow legal question in the first phase of this trial was which party, OBOT or the City, breached the agreements.” Specifically, “[e]ach [party] alleged the other breached the contracts. . . . OBOT asserted its performance was excused as set forth in its claims of force majeure, which the City improperly rejected.

The City contended the opposite—OBOT’s non-performance was not excused, and the City therefore correctly denied OBOT’s claims of force majeure and properly terminated the Lease on November 22, 2018.” And, Judge Wise ultimately concluded, “the City breached the Parties’ contracts.”

In support of her conclusions, Judge Wise set forth her “Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law,” broken down into two main parts. In the first part, Judge Wise quoted and adopted the findings of the federal district court (section III.A). In the second part, Judge Wise stated her findings of fact and conclusions of law “not addressed in the federal decision.”

This part in turn included two main subparts, the first of which essentially presented a 51-page discussion of the facts dating back to 2002 (the environmental review of the then proposed redevelopment plan of the Oakland Army base under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)) through November 22, 2018 (the termination of the Ground Lease) (section III.B.2 through 5). In the second subpart, Judge Wise, incorporating her prior findings, made findings specific to the parties’ competing causes of action (section III.B.6 through 10).

Findings Regarding Events Setting the Stage of the Parties’ Conflict

We set forth in some detail below Judge Wise’s findings and conclusions relative to the issues on appeal. But before doing that, we begin with a brief discussion of three items of evidence we find noteworthy, harbingers of the approach the City would take in its contractual relationship with OBOT—a relationship in which the City had a duty “ ‘ “of good faith and fair dealing.” ’ ” (Carma Developers (Cal.), Inc. v. Marathon Development California, Inc.(1992) 2 Cal.4th 342, 371 (Carma).) Those three items are:

(1) Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf and her “clear view on the matter”; (2) the “Cappio Memo”; and (3) the kickoff meeting. Here are Judge Wise’s discussion of these items.

11 Mayor Schaaf

To set the stage, Judge Wise discussed the parties’ conflict surrounding the issue of coal: “Between the time the Development Agreement was signed in 2013 and the Ground Lease was finalized in 2016, members of the public and City officials expressed concerns about health and environmental issues associated with coal. Libby Schaaf, who had served on the City Council from 2011 to 2015, began serving as the City’s mayor in 2015. Indicative of her clear view on the matter, on May 11, 2015, she sent an email to Mr. Tagami with the subject line: ‘stop all mention of coal now.’ In the body of email, she wrote:

“Dear Phil,

“I was extremely disappointed to once again hear [an executive of OBOT’s then proposed subtenant] mention the possibility of shipping coal into Oakland at the Oakland Dialogue breakfast. Stop it immediately. You have been awarded the privilege and opportunity of a lifetime to develop this unique piece of land.

You must respect the owner and public’s decree that we will not have coal shipped through our city. I cannot believe this restriction will ruin the viability of your project. Please declare definitively that you will respect the policy of the City of Oakland and you will not allow coal to come through Oakland.

If you don’t do that soon, we will all have to expend time and energy in a public battle that no one needs and will distract us all from the important work at hand of moving Oakland towards a brighter future.

“Best,

“Libby.”

And Judge Wise went on to find: “Mayor Schaaf was consistently and adamantly opposed to the Project including coal as a potential commodity, although she wanted the important community benefits associated with redevelopment of the army base. On October 22, 2015, she called Mr. McClure who was in his car at the time. Mr. McClure memorialized their conversation in a note he created approximately two hours after the call.

During the discussion, Mayor Schaaf stated she was going to meet and enlist the help of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg to fight the Project and ensure there would never be any coal shipped through Oakland. Mr. McClure said he was aware of Mr. Bloomberg’s support of the Sierra Club’s efforts to oppose coal-related power generation.

Mayor Schaaf stated she was convinced there was a business solution to this disagreement; she wanted Mr. McClure to present a resolution (including the proposed terms of a deal for the Project) in which OBOT would agree to never ship coal. She said the issue was so important to her she would do everything in her power to make sure no coal would come through Oakland—even if it meant killing the entire Project.

Mayor Schaaf reminded Mr. McClure that he grew up in Oakland and should know shipping coal through the City would not be tolerated.” As Judge Wise summarized it: “Mayor Schaaf was unequivocal—in her communications both at the time and during her testimony at trial—she did not want coal moving through Oakland irrespective of the fact the coal was destined for other countries.”7

NOTE: 7 Judge Wise later noted that according to news articles released after the federal court decision Mayor Schaaf and other City officials would also make the following statements: “Mayor Schaaf is quoted as saying: ‘We will continue to fight this battle on all fronts; not just today, but every day.’ [Citation.] Council Member Dan Kalb is quoted as saying: ‘I will do everything in my power to stand against attacks on the health and safety of our East Bay communities. The City should do whatever it takes within the law to make sure this coal terminal never gets built.’ [Citation.] Council Member Kalb is further quoted as saying: ‘We need to do whatever it takes within the law to hold firm in our opposition to this ridiculous proposal. The residents in that area, the workers of Oakland and the entire world need us to stop this export terminal.’ [Citation.]

The “Cappio Memo”

“[A]pproximately three months before the Ground Lease was executed, . . . the City’s Assistant City Administrator, Claudia Cappio, issued an interoffice memo, dated November 6, 2015,” which came to be called the “Cappio Memo.” The memo required the Planning and Building Department to notify three senior City officials upon receipt of any OBOT permit applications, and not to deem the application complete or issue permits without consulting them.

The memorandum applied only to OBOT, not any other City project. As to this, Judge Wise found that “the explanations of the City witnesses regarding the purpose of the Cappio Memo—to ensure that OBOT’s Project permits were efficiently processed with good communication and coordination throughout the various City offices—strained credulity given the Parties’ disagreement about coal when the Memo was written and because no witness from the City was able to identify any similar memo or protocol that had ever been implemented by the City on any other development project, regardless of size or complexity.”

The Kickoff Meeting

“On March 9, 2016, OBOT representatives and people from various departments in the City met for what the [p]arties referred to as the ‘kickoff’ meeting.” “[T]he representatives from OBOT expected that during the meeting the [p]arties would review the basis of design, discuss permitting and the permitting process, and would plan the next steps—generally, how the parties would work together to move the project forward.”

However, at the meeting “the City informed OBOT building permits would go through a discretionary (instead of administrative) review, and the City would conduct a commodity-by-commodity review of any commodity that would be transported through the Project. Further, the City indicated it might re-open 14a CEQA analysis for the Project.

Upon hearing this, Tagami left the meeting early because, the meeting ‘was not to kick off the project. It was to restart the land use process.’ ” Months after the kickoff meeting, the City enacted the no-coal ordinance and resolution.

Findings Regarding the City’s Continual Delay of the Project—and Its “Resolute Trajectory Toward Terminating the Lease”

Judge Wise found that in the years leading up to the federal court’s decision, and despite OBOT’s efforts to move the project forward, the City through its actions continually “cause[d] the Project to stagnate,” which actions she described in great detail—some 33 pages—in section III.B.2 through 4 of the statement of decision.

But even after the federal court issued its decision, the City continued to cause delays that, as Judge Wise explained in section III.B.5, demonstrated “the City’s resolute trajectory toward terminating the Lease.”

As Judge Wise put it, “When the Federal Decision was issued, OBOT believed the Project would immediately proceed with the full cooperation of the City. That is not what occurred.” She acknowledged that “the City had the right to appeal the Federal Decision” and that it was “appropriate and responsible for the City to explore every legaloption available to effectuate its legitimate interest in protecting the health and safety of its constituents.” And the City could have done so while, at the same time, “diligently, and in good faith, taken every reasonable step to move the Project forward . . . .” “What the City could not do was undermine or improperly terminate the contracts it had with OBOT—that was not a legal option. That, however, was the path the City selected.”

Judge Wise determined that “[t]he City’s conduct hamstrung OBOT, 1516 making it difficult, exceedingly impracticable or functionally impossible for OBOT to fulfill its own obligations under the Lease. . . .[¶]. . . the City then used OBOT’s inability to proceed as a pretext for terminating the Lease. In this instance, and each of the incidents the Court describes that occurred after May 15, 2018, the record discloses no good faith justification for the City’s conduct.

NOTE: 8 And, at trial, the City did not provide one. Considering the totality of the circumstances (specifically the City’s actions and omissions, the public statements made by City officials at the time, and the testimony and evidence at trial), the only reasonable inference is that the City wanted the benefit of the ordinance that was rejected (as a breach of the Development Agreement) in the Federal Decision—the City wanted OBOT to build a coal free Project or the City would stop the Project altogether.”

We summarize, in no particular order, examples of “the City’s actions and omissions” that Judge Wise found caused delay of the project and demonstrated the City’s intent to “stop the Project altogether”—actions and omissions that Judge Wise later listed in bullet-point fashion in her conclusions on force majeure.

Failure to clearly inform OBOT of permissible commodities The Development Agreement required the City to compile and deliver to OBOT before November 2013 a binder of local regulations that applied to the project. But “the City had not completed that task by the time the Ground Lease became operative on February 16, 2016.” The City eventually provided a list of existing, applicable City regulations in June 2016. Judge Wise found that although the City “complied with [its] obligation” to provide a binder of regulations, “the primary issue between the Parties was not the

NOTE: 8 All told, Judge Wise commented on the City’s lack of “good faith” at least 12 times in the statement of decision.

17 historic regulations that were applicable to the Project.” Rather, “[t]he issue was the moving target and general lack of clarity about what commodities, if any, the City would or would not permit to be shipped through the terminal, and what legal or regulatory basis the City would use to make those determinations.”

Judge Wise found that “when the City made it clear to OBOT that it would evaluate otherwise legal commodities on a ‘commodity by-commodity’ basis (beginning with coal)” at the March 9, 2016 kickoff meeting, “one of the critical items that was necessary to move the Project forward was the need for the City to inform OBOT, clearly and unequivocally, what commodities the City viewed as impermissible, and the legal basis for City’s position.”

Although “OBOT continued to seek clarification from the City about what commodities were potentially acceptable” after the no-coal ordinance and resolution, the City did not “provide[ ] OBOT with any specific guidance regarding what commodities could or could not be transported through the Project.” And, she held, the City’s failure to inform OBOT of permissible commodities made it practically “impossible” for OBOT to meet the Initial Milestone Date.

Failure to give OBOT feedback on the Basis of Design

In September 2015, OBOT submitted to the City “the Project’s Basis of Design,” which Judge Wise found “took a significant amount of time and money for OBOT to create . . . and comprised three volumes and about 1,500 pages of information.” “The City understood OBOT’s Basis of Design was a preliminary document. An iterative, collaborative process was necessary to advance the Project design: The City would provide feedback and direction, and OBOT would respond with changes and further detail.” And she found “that . . . one of the things that was necessary for the Project to proceed was 18 for the City to thoroughly review the Basis of Design and provide OBOT with clear, specific, and timely feedback.”

But the City failed to do so at any point and, Judge Wise concluded, without the City’s feedback on the Basis of Design, “it was unreasonable— and from a practical standpoint, impossible—for . . . OBOT to meet the Initial Milestone Date.”

Failure to use “commercially reasonable efforts” to enter into the Rail Access Agreement with the Port

The Ground Lease required the City to “use commercially reasonable efforts to enter into a Railroad Access Agreement with the Port.” As Judge Wise noted, “[t]he Project would connect to the Port of Oakland’s rail terminal via a rail corridor . . . . The ownership and easement rights within the entire rail corridor connecting the Port’s rail terminal with the West

Gateway property involved multiple entities. . . . Access to rail, owned or held by these parties, was essential to the Project.” Thus, “[e]arly in the redevelopment process, the Parties understood the Rail Access Agreement was key to development of the Project.” However, Judge Wise found, even “after the Federal Decision, the City continued to not ‘use commercially reasonable efforts to enter into a “Rail Access Agreement. . . .” ’ ” And she concluded: “[t]he City’s failure to do so, as well as its lack of transparent communication with OBOT regarding the [Rail Access Agreement], demonstrates a lack of good faith by the City to move the Project forward.”

Failure to complete the “public improvements” and to turn over the premises to OBOT to complete the private rail improvements “When OBOT signed the Ground Lease, the Parties understood, among other things, that the City was required to complete certain Public Improvements (such as, grading and drainage work) before OBOT could begin the private development of the rail corridors (e.g., installing ballast rock, ties, and rail).”

Despite OBOT’s repeated attempts to discuss with the City its progress on the public improvements, “the City had not completed the Public Improvements and turned over the rail corridor to OBOT (which would have allowed OBOT to complete that work)” before the City terminated the Ground Lease. Moreover, the City displayed “general apathy to substantively responding to OBOT’s reasonable requests,” conduct that “hamstrung OBOT, making it difficult, exceedingly impracticable or functionally impossible for OBOT to fulfill its own obligations under the Lease.”

Failure to substantively respond to OBOT’s force majeure notices, and instead issuing a notice of default and terminating the Ground Lease

On March 11, 2016, OBOT sent the City the first of many letters invoking the force majeure provision of the Ground Lease. OBOT asserted that the City’s failure to provide it with applicable construction codes and City regulations was a force majeure event that entitled OBOT to an extension to complete its obligations under the Ground Lease. OBOT reiterated this force majeure claim in subsequent letters of April 10, July 30, and August 3, 2018, adding in those letters that the City’s no-coal ordinance and resolution, in violation of the Development Agreement, constituted another act of force majeure.

The City did not provide any substantive responses to the letters. Instead, on August 20, 2018, the City sent a letter stating that OBOT failed to meet the Initial Milestone Date. The City acknowledged OBOT’s prior force majeure letters, but “elect[ed] to continue a deferral of its substantive response” to them.

OBOT responded on August 28, sending the City a letter explaining that it had “ ‘worked diligently and in good faith at every juncture to advance 1920 all aspects of this Project,’ ” setting forth its efforts to that effect, reiterating its earlier force majeure claims, and asking the City for “ ‘meaningful engagement’ ” to resolve the outstanding issues between them.

The next month, rather than directly respond to OBOT’s letter, the City sent OBOT a “ ‘Notice to Cure’ ” its asserted default for failing to meet the Initial Milestone Date—and rejected OBOT’s force majeure claims.

On October 4, OBOT sent another letter to the City repeating its force majeure claims, followed shortly thereafter by a 51-page letter in which OBOT contested the City’s claim that OBOT was in default of the Ground Lease and that in any event it had commenced the required cure of default.

On October 23, the City sent OBOT a “ ‘Notice of Event of Default,’ ” repeating its previous position that OBOT was in default for failing to meet the Initial Milestone Date and had failed to cure the default. The City demanded OBOT pay liquidated damages and contended that without any further notice the Ground Lease would automatically terminate on November 22, 2018.

OBOT nonetheless continued to send the City further correspondence that continued to reject the City’s determination that an event of default had occurred, but still requested that the City work collaboratively with it to move the project forward. Judge Wise found that “the City’s decisions to issue a Notice of Event of Default and terminate the Lease instead of substantively responding to any of the correspondence, . . . including OBOT’s force majeure claims, demonstrate the City’s lack of good faith to honor the

Lease and the other agreements between the Parties.” All this led to Judge Wise’s holdings on OBOT’s and the City’s competing causes of action. 21

The Holdings On The Causes of Action

Plaintiffs’ first and second causes of action for breach of contract were predicated on the force majeure provision of the Ground Lease. Judge Wise interpreted that provision to refer to events that “were sufficiently acute that it was impracticable or unreasonably difficult for OBOT to perform its Lease obligations.”

Doing so, Judge Wise rejected the City’s argument that the force majeure provision required “OBOT’s contractual performance” to “in fact be impossible.” Rather, Judge Wise noted the City’s additional argument that an event of force majeure must be unanticipated or unenforceable at the time the parties entered into the contract, going on to state she did not need to resolve that question, but in any event the City’s actions that caused OBOT’s non-performance were unforeseen and unanticipated. And Judge Wise concluded as follows:

“[C]onsistent with section 16.1 of the Ground Lease, OBOT’s performance of its Lease obligations were hindered, affected, or delayed the by each of the following acts by the City, each of which the Court finds is a separate event of force majeure:“• the City’s breach of the Development Agreement when it enacted a no-coal ordinance that was unsupported by substantial evidence (as determined in the Federal Decision) and applied that ordinance to the Project;

“• the City’s breach of the Development Agreement by failing to clearly and unequivocally inform OBOT what commodities the City viewed as impermissible, and the legal basis for the City’s position; “• the City’s breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing (previously described in this Statement of Decision) when it did not diligently advance the Project, and instead took repeated measures to terminate the Lease, after the Federal Decision;“• the City’s failure to provide substantive, written feedback to OBOT regarding the Basis of Design;“• the City’s failure to use commercially reasonable efforts to enter into the Rail Access Agreement with the Port; and“• the City’s failure to complete the Public Improvements and the related survey of the rail corridor, and its failure to turn over the property to OBOT to complete the private rail improvements.

“Except for the City’s breaches of the Development Agreement, each of these acts occurred after May 15, 2018,” the date of the federal court’s decision. Judge Wise then turned to plaintiffs’ fourth cause of action for breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. After setting forth the applicable law, Judge Wise determined that: “OBOT proved the City’s lack of good faith efforts to address various obstacles (some of which were created by the City) in OBOT’s path, and its unjustified termination of the Lease, prevented OBOT from receiving the benefits of the contracts.

As this Court repeatedly found in Section B.5 of this Statement of Decision, the City provided no justification for its actions and apathy; the only reasonable inference is that (particularly after May 15, 2018) the City was attempting to create leverage to require the Project be coal-free, despite (as the Federal Decision determined) the City’s failure to provide the necessary evidentiary foundation for such a condition.

Thus, the City sought concessions from OBOT that OBOT was not obligated to make. This cannot be described as conduct that is ‘fair and in good faith.’ OBOT proved it was harmed by the City’s conduct because the City terminated the Ground Lease, which stopped the Project. . . . The Court finds the City breached the covenants of good faith and fair dealing implied in the Ground Lease and the Development Agreement.”

Judge Wise next addressed the fifth cause of action for declaratory relief, which asked for a judicial declaration that OBOT “is not in default under the [Development Agreement] or the Lease.” “Based on the findings in this Statement of Decision,” Judge Wise “determined OBOT is not in default under the [Development Agreement] or the Lease.”

Judge Wise did not reach plaintiffs’ third cause of action for the City’s alleged anticipatory breach of Ground Lease, because she had “already determined that the City’s termination of the Ground Lease on November 22, 2018, constituted a breach of contract.” Nor did she reach the sixth cause of action for specific performance, explaining, “[s]pecific performance is an equitable remedy and not a cause of action” and deferred its determination on plaintiffs’ entitlement to such a remedy to the remedies phase of trial.

Finally, as to the City’s lawsuit, Judge Wise found that “[t]he City’s claims rely on the same facts the Court has already considered in this Statement of Decision. As a result, the Court finds the City failed to prove its claims against OBOT.”

The Remedies Phase

The remedies phase of trial began on November 28, 2023, and on December 22, Judge Wise issued another statement of decision in which she concluded that OBOT and OGRE were entitled to either (a) the equitable remedies of specific performance and declaratory relief, or (b) damages of $317,683, subject to OBOT relinquishing its rights to the project. OBOT elected the equitable remedies.

The Judgment and the Appeal

On January 23, 2024, Judge Wise entered a judgment in favor of OBOT and OGRE that: (1) declared that OBOT was not in default of the Ground Lease; (2) declared that the City’s terminations of the Ground Lease and 24 Development Agreement were invalid; and (3) ordered that the Initial Milestone Date be extended by a period of two years and six months from the date of entry of judgment.

That same day, the City appealed from the judgment. This is appeal number A169895, and award of attorney fees and costs totalling $6,572,880.44 in attorney fees and $276,805.90 in costs, for a total award of $6,849,686.34, as of this writing.

(For those who have asked how much the City of Oakland spent on the case, in 2023, the staffing cost was estimated to be $15 million. So, the City of Oakland is looking at, at the very least, losing $21 million.

The Awards of Attorney Fees and Costs

On May 3, Judge Wise issued an order finding OBOT was the prevailing party and awarding OBOT $6,572,880.44 in attorney fees. In a separate order filed that day, Judge Wise granted in part the City’s motion to tax costs, finding that certain claimed costs were not recoverable but that others were, and directed OBOT to submit supplemental briefing setting forth the “updated adjustments” of the recoverable costs. After receiving that briefing, on May 28, Judge Wise issued another order awarding OBOT $276,805.90 in costs.

On July 2, the City filed a notice of appeal from “[a]n order after judgment” which it noted was entered on May 3.9 This is appeal number A170849. The City acknowledges that it does “not contest here the amount of the fees or costs awards” and that it “filed the protective appeal only as to prevailing party status arising from judgment.” We subsequently granted

NOTE: 9 The notice of appeal attached (1) the May 3 order awarding OBOT attorney fees and (2) the May 3 order granting in part the City’s motion to tax costs. In the latter order, as noted, Judge Wise requested supplemental briefing. She also ordered that, after “resolving all the issues relating to costs, OBOT . . . must prepare a final order stating clearly what costs were sought, what costs were taxed, and the total amount of costs that the City must pay to OBOT.”

The final order setting forth the amounts of costs awarded was filed on May 28. We assume that the notice of appeal encompasses the two orders filed on May 3, as well as the May 28 order setting forth the amounts of the costs awarded to OBOT. 25 the parties’ joint request to consolidate the two appeals.

DISCUSSION

Some Appellate Principles

We start with the fundamental principles of appellate review, that the judgment is presumed correct, that all intendments and presumptions are indulged in favor of its correctness, and that the appellant bears the burden of affirmatively demonstrating error. (Jameson v. Desta(2018) 5 Cal.5th 594, 608–609; accord, Universal Home Improvement, Inc. v. Robertson(2020) 51 Cal.App.5th 116, 125.)

The doctrine of implied findings is “natural and logical corollary” to these fundamental principles. (Fladeboe v. American Isuzu Motors, Inc. (2007) 150 Cal.App.4th 42, 58.) Under that doctrine “the reviewing court must infer, following a bench trial, that the trial court impliedly made every factual finding necessary to support its decision.” (Id.at p. 48, italics added; accord, Eisenberg et al., Cal. Practice Guide: Civil Appeals and Writs (The Rutter Group 2024) ¶ 8:22 [under the doctrine, “the appellate court will presume that the trial court made all factual findings necessary to support the judgment for which substantial evidence exists in the record”].)

Seeking to avoid the doctrine of implied findings, the City relies on Code of Civil Procedure section 634, which provides that if the statement of decision does not resolve a controverted issue or is ambiguous, and the omission or ambiguity was brought to the attention of the trial court, “ ‘it shall not be inferred on appeal . . . that the trial court decided in favor of the prevailing party as to those facts or on that issue.’ ”

The City then asserts that “[a]s discussed herein [its opening brief], the trial court’s statement of decision contains notable omissions, including failing to address contract provisions, uncontroverted evidence directly on point, and in the case of OGRE, required elements. All were detailed in the City’s objections.” 26 Initially, as OBOT correctly observes, “the City never identifies any controverted issues that the [statement of decision] left unresolved.”

The City’s failure to articulate the purported omissions in the statement of decision or the substance of their objections to the proposed statement of decision allows us to disregard its argument. (See Cahill v. San Diego Gas & Electric Co.(2011) 194 Cal.App.4th 939, 956 [“ We are not bound to develop appellant[’s] argument for [it]. The absence of cogent legal argument . . . allows this court to treat the contention as waived. ”].) The City’s position is also unpersuasive.

The City’s objections regarding the claimed “omissions or ambiguities” in the proposed statement of decision cited to evidence that would have supported findings contrary to those found by Judge Wise or attacked the legal premises of her findings—in other words, mere disagreements with Judge Wise’s findings. However, Code of Civil Procedure section 634 “applies only when there is an omission or ambiguity in the trial court’s decision, not when the party attacks the legal premises or claims the trial court’s findings are irrelevant or unsupported by evidence.” (Duarte Nursery, Inc. v. California Grape Rootstock Improvement Com.(2015) 239 Cal.App.4th 1000, 1012.) The City’s purported objections were not valid objections.

Standard of Review

In entering judgment Judge Wise exercised her equitable powers to award the remedies of declaratory relief and specific performance. (See Caira v. Offner(2005) 126 Cal.App.4th 12, 24 [“Declaratory relief is ‘classified as equitable by reason of the type of relief offered’ ”]; Petrolink, Inc. v. Lantel Enterprises(2022) 81 Cal.App.5th 156, 165–166 [the remedy of specific 27 performance is a discretionary, equitable remedy].)10 In Husain v. California Pacific Bank(2021) 61 Cal.App.5th 717, 727 (Husain), quoting our Division Four colleagues in Richardson v. Franc(2015) 233 Cal.App.4th 744, 751, we said, “After the trial court has exercised its equitable powers, the appellate court reviews the judgment under the abuse of discretion standard.[Citation.]”

When applying the abuse of discretion standard, “the trial court’s findings of fact are reviewed for substantial evidence, its conclusions of law are reviewed de novo, and its application of the law to the facts is reversible only if arbitrary and capricious.” (Haraguchi v. Superior Court(2008) 43 Cal.4th 706, 711–712.) In applying the substantial evidence standard to findings of fact, “we consider the evidence in the light most favorable to the prevailing party, drawing all reasonable inferences in support of the findings.” (Thompson v. Asimos(2016) 6 Cal.App.5th 970, 981.) “[W]hether [a] question of fact is decided on conflicting facts, or even undisputed facts,” Judge Wise’s resolution of any such fact question “must be affirmed under the rule of conflicting inferences by which we must indulge all reasonable inferences in favor of [OBOT], the party that prevailed below.” (Husain, supra, 61

Cal.App.5th at p. 732; accord, Universal Home Improvement, Inc. v. Robertson, supra,51 Cal.App.5th at pp. 125–126.) “And . . . the rule applies

NOTEL 10 We note that it may be more than the remedies that involve equity, but perhaps even the merits analysis itself. In a case discussing the companion doctrine of frustration, Chief Justice Traynor said “[t]he question in cases involving frustration is whether the equities of the case, considered in the light of sound public policy, require placing the risk of a disruption . . . on defendant or plaintiff under the circumstances of a given case.” (Lloyd v. Murphy (1944) 25 Cal.2d 48, 53–54.)even where, as here, a court issues a statement of decision.” (Husain, at p. 732.)

Further, an appellant challenging the sufficiency of the evidence has the burden to set forth all the material evidence on the point, not only facts favorable to it. (Foreman & Clark Corp. v. Fallon(1971) 3 Cal.3d 875, 881 (Foreman).) This “burden ‘grows with the complexity of the record’ ” (Myers v. Trendwest Resorts, Inc.(2009) 178 Cal.App.4th 735, 739), and unless this burden is met, we may treat the substantial evidence issues as waived and presume the record contains evidence to sustain every finding of fact.

(Foreman, supra, 3 Cal.3d at p. 881.) The City’s opening brief, including in its statement of facts and argument section, presents a one-sided version of evidence, setting forth only evidence favorable to it—and ignoring evidence favorable to the judgment. This is especially problematic here given that the record is voluminous and complex.

As to questions of law subject to de novo review, such questions include the interpretation of a contract where the interpretation does not turn on the credibility of extrinsic evidence (People ex rel. Lockyer v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.(2003) 107 Cal.App.4th 516, 520) and the application of resjudicata or claim preclusion. (City of Oakland v. Oakland Police & Fire Retirement System(2014) 224 Cal.App.4th 210, 228.)

Finally, under the abuse of discretion standard, we determine whether the trial court’s application of law to the facts “ ‘falls within the permissible range of options set by the legal criteria.’ ” (Husain, supra, 61 Cal.App.5th at p. 727.) In other words, to demonstrate an abuse of discretion, the City must show that Judge Wise’s decision “ ‘is so irrational or arbitrary that no reasonable person could agree with it.’ ” (Sargon Enterprises, Inc. v. University of Southern California(2012) 55 Cal.4th 747, 773; accord, 28Haraguchi v. Superior Court, supra, 43 Cal.4th at pp. 711–712.)

The City makes no such showing.

Judge Wise Properly Concluded Force Majeure Applied

As noted, the Ground Lease had a “Force Majeure” provision that provided that a party “whose performance of its obligations hereunder is hindered or affected by events of Force Majeure shall not be considered in breach of or in default in its obligations hereunder to the extent of any delay . . . .” and that a party may seek an extension of time to perform its obligations with notice to the other party.

And Article 40 defined the term: “Force Majeure means events which result in delays in Party’s performance of its obligations hereunder due to causes beyond such Party’s control, including, but not restricted to, acts of God or of the public enemy, acts of the government, acts of the other Party . . . .” (Underlines omitted.)

As also noted, Judge Wise found force majeure, indeed in six specific respects. The City argues that Judge Wise’s holding is “Contrary to the Ground Lease and California Law,” an argument that has four subparts, the first of which is “force majeure does not Supersede Express Terms.”

The City’s argument addresses Judge Wise’s holdings one-by-one, though in an order different from her. OBOT states in its brief—a statement with which the City does not take issue in its reply—that “OBOT need only establish that it was entitled to an extension under any one of the six categories for this Court to affirm.” We will address them all—and conclude that in each of them Judge Wise was right. But before we do, we briefly discuss force majeure.

Force majeure is a French term meaning “superior force” and has its origins in the early law of “impossibility.” (See generally 1 Witkin, Summary of Cal. Law (11th ed. 2025) Contracts, § 853.) It was, the author says, “the principal impossibility defense.” (Ibid.) Over 75 years ago, our Supreme 2930 Court had before it a case that involved the cowboy actor Gene Autry who claimed that his military service allowed him to terminate his agreement with defendant producer of Western photoplays: Autry v. Republic Productions, Inc.(1947) 30 Cal.2d 144 (Autry). The trial court ruled for defendant, holding that after his discharge Autry was bound to carry out the unperformed portion of the contracted employment. (Id.at p. 147.)

The Supreme Court reversed. Doing so, the court said this about “impossibility”: “ ‘Impossibility’ is defined in section 454 of the Restatement of Contracts, as not only strict impossibility but as impracticability because of extreme and unreasonable difficulty, expense, injury, or loss involved.

Temporary impossibility of the character which, if it should become permanent, would discharge a promisor’s entire contractual duty, operates as a permanent discharge if performance after the impossibility ceases would impose a substantially greater burden upon the promisor; otherwise the duty is suspended while the impossibility exists. (Restatement of Contracts, § 462.)” (Autry, supra, 30 Cal.2d at pp. 148–149.)

An exhaustive annotation first published in 1962 in American Law Reports is entitled, “Modern status of the rules regarding impossibility of performance as defense in action for breach of contract.” (Annot. (2024) 84 A.L.R.2d 12.) Section 9[b] of the annotation is entitled, “Liberalized rules as to supervening impossibility; implied or constructive conditions; major changes in circumstances going to foundation of contract—Implied or constructive condition of contract.” (Id., § 9[b].) Section 11 is entitled

“Expanded meaning of impossibility; concept as extending to extreme impracticability.” (Id., § 11.) And section 12[b] is entitled, “Impossibility caused by or attributable to a contracting party—Impossibility caused or preventable or remediable by promisee.” (Id., § 12[b].) 31 In those sections are various observations about the evolution of the doctrine, including this in section 9[b]: “Williston brings out that the courts found it to be easier to evade the earlier doctrine as to impossibility by giving a new construction to certain promises than to overthrow the doctrine directly, and ‘it became a frequent mode of expression to say that where impossibility constitutes an excuse for failing to perform the terms of a promise, it is because there is an ‘implied condition’ in the promise, without noting that such a condition is ‘constructive,’ that is, based on other reasons than the expressions of the parties.’ 6 Williston, Contracts (Rev ed) § 1937.” (84 A.L.R.2d 12, § 9[b].)

And this in section 12[b]: “A standard treatise states that if the impossibility of performance arises directly or even indirectly from the acts of the promisee, it is a sufficient excuse for nonperformance by the promisor. This is upon the principle that he who prevents a thing may not avail himself of the nonperformance which he has occasioned. Nonperformance of a contract in accordance with its terms is excused if performance is prevented by the conduct of the adverse party. 12 Am Jur, Contracts § 381.” (84 A.L.R.2d 12, § 12[b].)

The Findings of Six Events of Force Majeure Do Not Conflict With Any Terms of the Ground Lease or California Law

The City’s primary argument, in a heading that “Force Majeure Does Not Supersede Express Terms,” is this: “Each of the six events of Force Majeure found by the trial court was already addressedby specific terms of the Ground Lease in which the parties defined their performance obligations and allocated risk, often with exclusive remedies.

The trial court’s interpretation of the force majeure provision effectively nullified those terms and the risk allocation agreed to by the parties, contrary to California law, which has long held that a general force majeure clause does not override 32 more specific contract terms.” The City goes on to cite, without discussion or analysis, five cases setting forth boilerplate principles of contract law. The principles have no application here. And the City’s argument is not persuasive.

1. The Ordinance

Citing to section 5.1.1.2 of the Ground Lease, the City asserts that the Ground Lease “expressly contemplatedthe risk that the City might pass new laws, that OBOT might challenge those laws, and OBOT agreed to perform anyway.” Section 5.1.1.2 of the Ground Lease does not say what the City says it does.

Section 5.1.1.2 states that no law “shall relieve or release [OBOT] of its obligations hereunder” or shall “give [OBOT] any right to terminate this Lease.” OBOT never sought to be “relieved” of any obligation or to “terminate” the Ground Lease, but rather to perform within an extended time period—to which, we note, it was entitled under the required schedule provision (section 6.1.1) that expressly makes OBOT’s obligation to meet the Initial Milestone subject to extension rights under the force majeure clause.

The City contends only that OBOT failed to commence construction by the Initial Milestone. But at all times before the judgment in the federal case the City verified in writing that OBOT was in compliance with all obligations under the Ground Lease. It was only after that adverse judgment that the City changed its position and claimed default.

Citing section 6.1 of the Ground Lease, the City argues that OBOT assumed the risk of the City’s legislative action, noting that the section references the construction of a terminal “ ‘capable of servicing one or more lines of export products.’ ” But, as Judge Wise found, the evidence established that the City made it practically impossible for OBOT to build any terminal. In light of OBOT’s insistence that it had the right to ship coal 33 through the terminal, and OBOT’s ongoing challenge to the no-coal ordinance, the City was simply unwilling to cooperate in terminal design or allow OBOT to advance construction.

So, as Judge Wise also found, the City was unwilling to allow OBOT to build any terminal lest the federal court strike down the no-coal ordinance and leave the City with no means to prohibit coal. Nothing in section 6.1 negates OBOT’s rights under the force majeure provision for the City’s intentional obstruction.

2. The Refusal to Confirm Commodities

The City argues that Judge Wise’s conclusion that its failure to provide OBOT “with a list of approved and disapproved commodities was Force Majeure . . . is also contrary to contract language—and, potentially, state law.” The argument is based on the assertion that under article 5 of the Ground Lease OBOT essentially “agreed that the City . . . made no promises regarding regulatoryapprovals for [the] project”; and that Judge Wise nevertheless “faulted the City for not making those promises and providing regulatory certainty by telling OBOT what it could and could not ship . . . .”11

And, the City goes on, “it would be a massive change in the law if everygovernment contractor could invoke force majeure to evade obligations because the government failed to advanceregulatory certainty. The trial court’s holding plainly contradicts Article 5.” The hyperbole is misplaced. To begin with, the City mischaracterizes the context of OBOT’s requests. When the parties signed the Ground Lease, there was no

NOTE: 11 Judge Wise acknowledged that “nothing in the Ground Lease . . . obligated the City to provide with a list of ‘approved’ commodities,” but faulted the City for failing to provide OBOT the commodity clarity it requested. 34

“regulatory uncertainty” about permissible commodities: the CEQA process had been completed and the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) and zoning for the project made clear OBOT’s right to transport coal and other commodities. As Judge Wise put it, it was unnecessary for the parties to include a provision in the Ground Lease to approve commodities “because, until the City suggested otherwise, the Project could presumably handle any legal bulk commodity.” The claimed “regulatory uncertainty” arose only from the ordinance, and it was in light of this—and with the goal of trying to move the project forward—that OBOT sought clarity whether the City would approve anycommodities. The City refused to provide any such clarity,

NOTE 12 which delayed and hindered terminal construction because OBOT and OGRE could not complete the basis of design without knowing which commodities could be handled.

This was the reason Judge Wise found that for OBOT to be able to advance terminal construction, it needed the City “to thoroughly review the [basis of design] and provide OBOT with clear, specific, and timely feedback.” The City next argues with Judge Wise’s factual finding that the City breached the Development Agreement.

To no avail, as substantial evidence supports that finding. The federal court decision confirmed that the Development Agreement gave OBOT the right to build a terminal that could handle coal (Oakland Bulk & Oversized Terminal, LLC v. City of Oakland, supra, 321 F.Supp.3d at p. 989), and the evidence here established multiple City acts intended to delay and hinder terminal development as an end-run around that decision and the Development Agreement.

These acts included the City’s failure to: (1) rely on the existing EIR to the fullest extent as required by section 3.5.1 of the Development Agreement; (2) apply the then existing Construction Code as a ministerial act as required by section 3.4.4; and (3) meet and confer with OBOT about any claimed breaches as required by section 8.4.

12 As to this, we note that the City made no secret of its actions and, as Assistant City Administrator Elizabeth Lake admitted, construction was delayed due to these “local policy decisions”

Finally, the City argues that requiring it to “pre-approve or reject” commodities raises “serious constitutional concerns.” But OBOT did not seek pre-approval of commodities. The EIR and zoning already established the approved commodities, including coal, that could be shipped through the terminal. OBOT merely wanted the City to honor OBOT’s contractual rights to construct a terminal through which such commodities could be transported.

3. The Refusal to Provide Basis of Design Feedback

The City argues that Judge Wise “invented” a requirement that the City provide “substantive, written feedback” on the basis of design for the terminal. We see no invention. The Ground Lease provides a process for approving “construction documents,” defined to include schematic drawings, preliminary construction documents, and final construction documents.13 Once construction documents are submitted, the City has 30 days to approve or disapprove them; and if the City finds the construction documents to be incomplete, it

NOTE: 13 The City also raises a factual issue about whether the 2015 basis of design contained “schematic drawings.” Article 40 of the Ground Lease defines that term as “conceptual drawings in sufficient detail to describe a development proposal.” The evidence established that the basis of design contained schematic drawings. In fact, the City contended that OBOT’s 2015 basis of design was substantially identical to its 2018 basis of design; and when OBOT submitted the basis of design in 2018, the City acknowledged that the basis of design contained schematic drawings. 36

…has 21 days to inform OBOT. To facilitate the design process, the Ground Lease required the City to “communicate and consult informally as frequently as is necessary to ensure that the formal submittal of any Construction Documents to [the City] can receive prompt attention and speedy consideration.”

Finally, section 6.2.6.1 of the Ground Lease prohibited OBOT from commencing construction until the City approved the final construction documents and OBOT obtained all construction permits. OBOT submitted the basis of design to the City in 2015, which the City understood was a preliminary document that needed feedback. But the City never provided any such feedback, neither approval, nor denial, nor a notice of incomplete documents. Judge Wise properly found the City hindered and affected OBOT’s performance—and its ability to meet the Initial Milestone.

The City apparently argues that, notwithstanding its refusal to cooperate and provide feedback on the terminal design, OBOT could have “deemed the documents approved” under section 6.2.1 of the Ground Lease.

Not only does section 6.2.1 contain no requirement that OBOT do anything, the section provided OBOT with no practical ability to advance construction, as that section is subject to section 6.2.6.1, which prohibited OBOT from commencing construction without City approval of the final construction documents. Thus, Judge Wise rejected the City’s arguments that OBOT was “obligated to spend countless additional millions of dollars and time to advance the development of the Project that would transport unknown commodities.”

The City also argues that Judge Wise ignored OBOT’s statements in 2016 letters that review of the basis of design at that time would be premature. But the letters were sent in the context of the City’s health and safety investigation intended to support the no-coal ordinance. The letters 37 note that the basis of design represents approximately ten percent of the terminal design and that because the terminal is a “purpose-built facility,”

“OBOT must know which commodity(ies) are confirmed for shipping through it” before it can complete the design.

4. The Failure to Execute The Rail Access Agreement

The City argues, in a brief 12 lines, that Judge Wise “disregarded express contract terms in concluding that the City’s failure to use ‘commercially reasonable efforts’ to enter into the [Rail Access Agreement (RAA)] with the Port qualified as Force Majeure.” The argument is that “[t]he RAA was an operationsagreement,” that the Ground Lease did not make “OBOT’s construction deadlines contingent on execution of this document,” that OBOT “explicitly waivedthe completion of the RAA,” and that “the parties set no deadline, let alone one prior to the Initial Milestone, for its completion.”

And the City adds, “[t]he parties further recognized that the City and Port might fail to execute an RAA, and in that event OBOT would have, as a ‘sole and exclusive remedy,’ the right to ‘terminate the Lease.’ ”The evidence showed that the City intentionally delayed execution of the RAA with the Port as long as the City’s dispute with OBOT over coal persisted. The evidence also showed that the City’s failure to timely enter into the RAA hindered OBOT’s ability to build the Minimum Project Rail Improvements.

OBOT needed access to the rail right of way to be able to complete the rail components of the Minimum Project, but the City never turned over possession of any portion of the rail right of way. Moreover, the rail improvements would never be constructed in the absence of an easement or other use agreement that ensured the tracks could be used over the 66-year lease term. And without rail, it would be “impossible” to operate the Terminal because bulk commodities are transported by rail. 38

As to the City’s argument that section 5.2.3(a) limits OBOT’s remedy to termination of the Ground Lease, it fails for several reasons. First, this mischaracterizes section 5.2.3(a), which provides that “in the event that, notwithstanding City’s exercise of commercially reasonable efforts, the City is unableto enter the Rail Access Agreement, then [OBOT] may elect. . . as [OBOT’s] sole and exclusive remedy . . . to terminate the Lease.” (Italics added.) The City’s interpretation would render the words “may elect” superfluous. Such interpretation is improper. (Wells v. One2One Learning Foundation(2006) 39 Cal.4th 1164, 1207 [“interpretations which render any part of a statute superfluous are to be avoided.”].)

Second, the City’s exercise of commercially reasonable efforts and inability to enter the RAA are express preconditions to the termination remedy in section 5.2.3(a). The evidence showed, and Judge Wise found, that the City failed to use commercially reasonable efforts to enter the RAA.

Neither party contended that the City was “unable” to enter the RAA. Instead, the evidence established that the City and the Port agreed to RAA terms, but that the City failed to execute due to the coal dispute. Finally, nothing in section 5.2.3 suggests that the city’s failure to use commercially reasonable efforts to enter the RAA was exempted from events of force majeure. And nothing in the Ground Lease―or the law―permits the City to impose on OBOT the City’spreferred remedy, termination, for the City’s obstruction, especially as such a “remedy” would have resulted in a forfeiture by OBOT of its multimillion dollar investment in the project—not to mention reward the City for its bad faith breaches.

5. The Failure to Timely Complete The Public Improvements

The City argues that Judge Wise’s conclusion that the “City’s supposed failure to ‘complete the Public Improvements’ and the related survey of the Rail Corridor” was a force majeure event “conflicts with express contract language,” and that section 37.9.2(b) of the Ground Lease precluded such a finding and limited OBOT’s remedy to termination.

While section 37.9.2(b)requires the City to “commence construction of the Funded Public Improvements and diligently prosecute the same to Completion,” the section expressly acknowledges that such completion is “subject to any delays for Force Majeure.” Moreover, substantial evidence showed that the City’s delayed completion of the Public Improvements delayed OBOT’s performance.

The City’s argument that section 97.9.2(b) precluded OBOT from exercising its force majeure rights is also wrong. Like section 6.2.1 and the Rail Access Agreement discussed above, section 37.9.2 provides for an election of remedies for the City’s failure to complete public improvements: “Tenant may elect. . . to terminate this Lease . . . .” (Italics added.) Once again, the City’s interpretation would render the election language superfluous.

Violation of The Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing

As to Judge Wise’s sixth bullet point item of force majeure—violation of the covenant of good faith and fair dealing—the City argues that, as it will demonstrate in its “next argument” in its brief, “the City did not breach the implied covenant.” As will be seen, we disagree.

The Finding that OBOT Did Not Anticipate the City’s Actions Is Supported By the Record

Judge Wise found that each of the City’s actions was “unforeseen and unanticipated.” The City’s second sub-argument on force majeure is that “[e]ach ‘event’ of Force Majeure was anticipated.” The City suggests in a footnote that Judge Wise’s finding is contradicted by “record evidence,” but fails to cite any such evidence, no evidence to suggest, let alone demonstrate, 40 that OBOT anticipate the several years of the City’s efforts to thwart OBOT’s performance.

The City asserts that “[f]oreseeability in this case is established in the plain terms of the contract,” that “each of the court’s Force Majeure ‘events’ pertains to terms that already allocate risk and address the parties’ respective obligations,” but cites only to its several pages “supra” addressing one-by-one Judge Wise’s findings of force majeure events. We have resolved those issues against the City. Nothing more need be said here.

The Force Majeure Events Were Supported

The City’s third sub-argument is that Judge Wise “failed to connect any of the alleged events of force majeure to OBOT’s actual performance obligations.” (Capitalization and boldface omitted.) The argument begins by asserting that Judge Wise erred by “reasoning that each ‘force majeure’ event interfered with the project without closely analyzing OBOT’s actual performance obligations. A force majeure event must make it impossible or legally impracticable to perform specific contractual obligations,” citing three cases: Oosten v. Hay Haulers Dairy Employees & Helpers Union(1955) 45 Cal.2d 784 (Oosten); KB Salt Lake III, LLC v. Fitness International, LLC (2023) 95 Cal.App.5th 1032 (KB Salt Lake); and West Pueblo Partners, LLC v. Stone Brewing Co., LLC(2023) 90 Cal.App.5th 1179 (West Pueblo).

The City then goes on to assert that the specific requirements of section 6.2 of the Ground Lease “are neverdiscussed in the decision” and, the City asserts, “OBOT failed to take anyof the steps available to it to advance the design and construction of a terminal . . . .”

To begin with, the cases hardly support the City’s position. Oostensaid the doctrine of impossibility of performance is “not only strict impossibility but [also] impracticability.” (Oosten, supra, 45 Cal.2d at p. 788.) KB Salt Lakesaid that “ ‘[i]mpossibility is defined “as not only strict impossibility but [also] impracticability because of extreme and unreasonable difficulty, 41 expense, injury, or loss involved.” ’ ” (KB Salt Lake, supra, 95 Cal.App.5th at p. 1058.) And in West Pueblo, we held that the words “delayed” and “interrupted” in a force majeure provision did not mean “unable to,” explaining such “reasoning would obviate the doctrine of impracticability, as any performance obligation short of an impossible one could be satisfied at sufficient expense.” (West Pueblo, supra, 80 Cal.App.5th at p. 1191.)

Indeed, citing West Pueblo(along with the force majeure provision), Judge Wise rejected the City’s arguments that she was required to interpret the operative words in the provision—“delays,” “hindered,” or “affected”—as “impossible” or “at any cost” because such reasoning “would obviate the doctrine of impracticability” and is “not the standard.” Interpreting those terms in the context of the Ground Lease, the force majeure provision, and case law, Judge Wise stated the standard this way: “whether the City’s acts were sufficiently acute that it was impracticable or unreasonably difficult for OBOT to perform its Lease obligations.”14 We see no error there.

As noted, our Supreme Court in 1947 quoted the Restatement of Contracts that “ ‘Impossibility’ is defined . . . as not only strict impossibility but as impracticability because of extreme and unreasonable difficulty, expense, injury, or loss involved.” (Autry, supra, 30 Cal.2d at pp. 148–149.)

The new Restatement says, “Although the rule stated in this Section is 14 Judge Wise also found that the City’s strained interpretation, if accepted, would render the force majeure provision superfluous by eliminating the only remedy available under it. As she put it, “Interpreting the Lease’s Force Majeure provision to require actual impossibility would also negate the only remedy the Parties’ negotiated—more time. If OBOT’s contractual performance had to in fact be impossible, then no amount of time or money would have allowed OBOT to perform its obligations under the Lease. The Court will not read the Lease’s Force Majeure provision to render its only remedy, meaningless.” 42 sometimes phrased in terms of ‘impossibility,’ it has long been recognized that it may operate to discharge a party’s duty even though the event has not made performance absolutely impossible,” going on to state its election to use the word “ ‘impracticable’ . . . to describe the required extent of the impediment to performance.” (Rest.2d Contracts, § 261.)

And the annotation of the “modern” cases talks in terms of an “implied condition in the promise” or that non-performance “is excused if performance is prevented by the conduct of the adverse party.” (84 A.L.R.2d 12, §§ 9[b], 12[b].)

The City’s sub-argument asserts that Judge Wise “side-stepped the required showing of OBOT’s diligence with respect to actual contract requirements with a conclusory footnote claiming OBOT ‘acted with skill, diligence, and good faith.’ ” Then, after suggesting that OBOT supposedly admitted it voluntarily elected not to proceed with the terminal for financial reasons, the City concludes that the footnote “did not employ the correct legal standard (by ignoring the contract requirements) and was not remotely supported by substantial evidence.”

OBOT did not admit either that (1) it could have pursued the construction of a terminal to ship commodities other than coal or (2) financial reasons had any impact on the terminal. On the first point, OBOT did what it could to design and build a terminal through which commodities like soda ash could be shipped. But the City refused to allowed OBOT to proceed, lest OBOT use that terminal to ship coal.

In sum, there was voluminous evidence that the City failed and refused to cooperate with terminal design for any commodity. On the second point, the evidence demonstrated that OBOT and OGRE stand to make millions from the terminal; have the financial resources to construct the terminal; and have every incentive to build it as soon as 43 possible.